( Astrid Ackermann )

Recorded voice: “Where to? Carnegie Hall, please. Okay, here are your tickets. Enjoy the show. Your tickets, please. Follow me.”

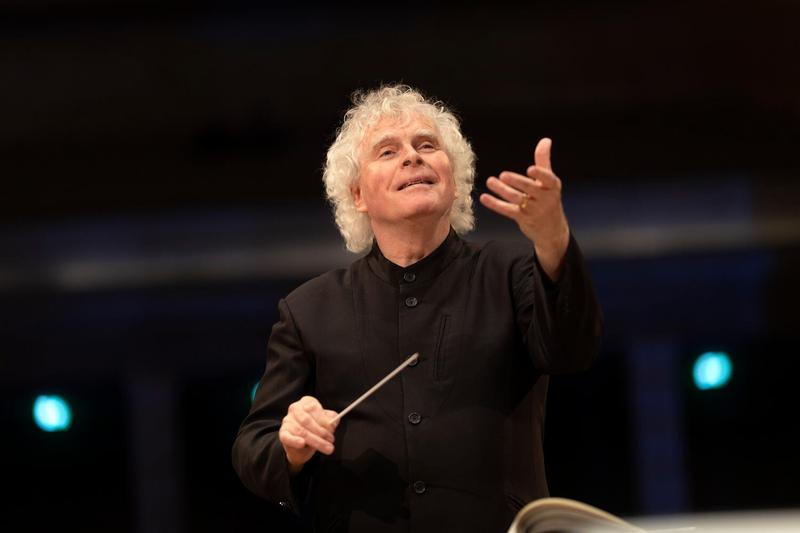

Jeff Spurgeon: On this Carnegie Hall Live broadcast, we have an orchestra from Munich, Germany. The Bavarian Radio Symphony is returning to Carnegie Hall with their new chief Music Director, Sir Simon Rattle. Sir Simon, of course, one of the top conductors in the world with long histories at the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the London Symphony as well. But tonight, with the Bavarian Radio Symphony.

Backstage at Carnegie Hall for this concert, I'm Jeff Spurgeon, alongside John Schaefer.

John Schaefer: Yes, and we are here with many of the members of said orchestra, sort of hemmed in backstage by the members of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Jeff Spurgeon: I'm sure they'd like to go out, but the stage door is closed, so they're back with us for a while.

John Schaefer: Now Jeff, as you alluded to, this is the first season for Sir Simon Rattle as Chief Conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony. But he is no stranger to this orchestra. He's guest conducted them a number of times over the years. And his first encounter with the orchestra goes back even further.

Sir Simon Rattle: I had heard them for the first time when I was 16 in Liverpool, when Kubelik came to conduct the Beethoven Ninth.

This was for me as a young conductor, a totally life changing experience. Although I had seen great orchestras and great conductors by that age, I had not seen an orchestra with their conductor who seemed to breathe as one in that way, where the communication backwards and forwards seemed so seamless and emotional.

John Schaefer: That is Sir Simon Rattle remembering the first time he saw this orchestra when Rafael Kubelik was directing them.

The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra was actually led by the Latvian conductor Mariss Jansons for 16 years until his passing in 2019. Jansons and Rattle were good friends, and as we mentioned, Sir Simon would often guest conduct this orchestra, and he remembers his first time behind the podium.

Sir Simon Rattle: From the first moment I met them, I realized within 15 minutes of the first rehearsal that this was going to be a relationship that I would treasure. You don't often get that, but that feeling of, oh, we are meant to be working together. I just presumed I would come a couple of weeks a year for the rest of my working life and always look forward to it.

Coming here simply felt very natural, and it's like having the largest string quartet on the planet.

Jeff Spurgeon: It's a nice description of an orchestra, about the intimacy and the familiarity with which they play, the largest string quartet on the planet.

It's going to be an interesting performance tonight. We have a big Mahler symphony, the number six on the second half of the program. That's the one with the big hammer blow and all the cowbells. We'll hear more about that later. But in the first half of the program, two lesser heard, but really fascinating works. Both of the pieces that we'll hear in the first half of this program were written between the First and Second World Wars.

John Schaefer: And specifically during the time of the Weimar Republic, in keeping with Carnegie's theme this season called Dancing on a Precipice. The which is about the music and the art and the culture of the Weimar Republic in Germany between the First and Second World Wars. The first of the two pieces is by Paul Hindemith and the second is by Alexander Zemlinsky.

And Sir Simon Rattle tells us that he enjoyed finding repertoire like this for this assignment.

Sir Simon Rattle: Find a something if you can, and that, that's wonderful because it's like gold mining, but it's seeing what can tell a story with Mahler that makes sense, and there's something about the biting wit of Hindemith and the depth of Zemlinsky that seems to me to make a very good menu with the Mahler, and then speak to the Mahler in another way.

Jeff Spurgeon: The Paul Hindemith work is the first one up. It's called Ragtime, and in parenthesis, the words "Well Tempered" are added. And from those words, you might guess that there is some Bach influence in this piece. And, in fact, in this short but very enthusiastic orchestral piece, you will hear a sort of jazzy take on the subject from the C minor Fugue in the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier. Ba ba dum bum bum, ba ba dum bum bum. That's the theme and, and Hindemith is going to play with that in a wild and very fantastically fun way.

The second piece on the program is of an entirely different nature. It's by Alexander Zemlinsky, who set to music, poetry, in German, by writers of the Harlem Renaissance. Collected into a book that was widely read in German speaking lands in the 1920s, early 30s. Sir Simon Rattle talked about what it was like to encounter these Zemlinsky settings.

Sir Simon Rattle: We were stunned by the immediate emotional impact of these pieces on both us as musicians and the audiences. And of course Lester Lynch is a very,, very special and charismatic communicator. And he tells the stories in a very remarkable way.

John Schaefer: Lester Lynch is the guest singer for that work by Zemlinsky on tonight's concert. Although he is an American singer, he has an international career. Actually made his debut at La Scala in Milan in a production of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess.

And in a note in the program book for tonight's concert, Lester Lynch suggests one possible reason why that Zemlinsky piece is not more commonly heard, which is that some of the writing by the Harlem Renaissance poets confronted racism in often harsh ways. And Jeff, even in German translation, the use of the N word in one of the poems is still troubling and provocative in the way that it was meant to be.

Jeff Spurgeon: That's exactly right. And it's it's going to be fascinating to hear these works because this will be the Carnegie Hall premiere of this set of pieces. They've never been performed before. They aren't heard very often. As you mentioned they were performed once in the 1930s and then they disappeared for several decades before they performed even a second time. So these are remarkable works to hear, and they reflect the atmosphere in which they were written, the Harlem Renaissance in New York in the 1920s and 30s, but also, but also what Zemlinsky was going through in the 1920s and 30s in his part of the world.

John Schaefer: As a German Jew. Austrian Jew, yeah.

So that'll be the Symphonic Songs by Zemlinsky. You don't have to wait too long for them because the opening piece is quite short. Paul Hindemith was, Jeff, as you mentioned, a Bach aficionado. He wrote a book about him called Johann Sebastian Bach, Heritage and Obligation.

But Hindemith was also a jazz fan. We know that he attended a Duke Ellington concert at the Cotton Club when he was in New York. So those two worlds meet in this first piece, and our conductor, Sir Simon Rattle, loves this early work by Hindemith.

Sir Simon Rattle: He's in his early twenties. He's just having fun. He's being a naughty boy, and he's enjoying everything that is around.

There's a feeling kind of out there in the world that this was sometimes a very serious and very worthy composer, even if a great one. It's good to remind people of also how far out and how radical he was, particularly in his 20s. And it's really, you know, it's also typical of the Weimar thing is to just mix it all together. I mean, it's less than four minutes, but it's a little piece of heaven.

Jeff Spurgeon: And speaking of a little piece of heaven, the stage doors have opened here at Carnegie Hall and the orchestra has gone out on stage. So what we understand is there was a long line at the box office and that is why the start of this concert is well, it had been delayed a little bit.

They just wanted to get everybody in the house as much as they possibly could, but now on stage the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra standing to receive the applause of this Carnegie Hall audience in anticipation of a very special concert tonight at Carnegie.

John Schaefer: So the first piece by Paul Hindemith is a work that was written relatively early in his career. By the time the 1930s rolled around, Hindemith was persona non grata to the Nazi regime that took over after the fall of the Weimar Republic. Part of that due to an opera he'd written called Sancta Susanna about a nunnery that was not exactly following the rules of celibacy, and the Nazi chief propagandist Joseph Goebbels denounced Hindemith, calling him an atonal noisemaker.

He would eventually emigrate to Switzerland, then to the U. S., where he taught at Yale and a bunch of other colleges, became a U. S. citizen, but eventually moved back to Switzerland.

And this piece, called Ragtime, subtitled Well-Tempered, will be a a colorful opener for this program by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

A packed house here tonight, and Jeff, we understand that the conductor Marin Alsop and the pianist Yuja Wang were part of that long line of people waiting to get into the hall tonight to see this performance.

Jeff Spurgeon: There's been a lot of anticipation of the appearance of this orchestra in the United States, spending a little time in the country these days. Having played in Washington just a couple of nights ago to a great review.

And now, on stage, Sir Simon Rattle, the new Chief Conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Warm reception from the audience, he shakes hands with Concertmaster Radoslaw Szulc. Those cheers are for Sir Simon. And we begin with Paul Hindemith’s Ragtime, from Carnegie Hall Live.

MUSIC: HINDEMITH Ragtime (Well-Tempered)

John Schaefer: The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Simon Rattle, opening this concert with a brash and jazzy tribute to Bach by Paul Hindemith. The piece is called Ragtime (Well-Tempered).

And we're going to stay in 1920s Europe now with a work next by Alexander Zemlinsky, his Symphonische Gesänge, or Symphonic Songs, set to texts that are poems by Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen, and Frank Smith Horne, writers of the so-called Harlem Renaissance.

And our singer tonight joining the orchestra is the American baritone Lester Lynch, and Jeff, this piece was only heard once, a Czech radio broadcast in 1935, and then remained totally unperformed as far as anybody knows until Baltimore in the 1960s.

Jeff Spurgeon: Poems are very powerful about the Black experience in the United States and Sir Simon Rattle told us about one of these poems that particularly touched him.

Sir Simon Rattle: As I started working through the score, the first things that struck me is that the poem by Langston Hughes, the first poem about lynching, and at the very end of the movement, after the singer's asked, “The white Lord Jesus, why should I pray now?”

Jeff Spurgeon: And now on stage, Sir Simon Rattle and baritone Lester Lynch, ready to bring you some very powerful music, and the first performance of these works in Carnegie Hall.

Alexander Zemlinksy's Symphonic Songs with texts by writers of the Harlem Renaissance from Carnegie Hall Live.

MUSIC: ZEMLINSKY Symphonische Gesänge, Op. 20

Jeff Spurgeon: Cheers for baritone Lester Lynch and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Simon Rattle. The orchestra members on their feet as well, with applause for the soloist in this first ever Carnegie Hall performance of Alexander Zemlinksy's Symphonische Gesänge, Symphonic Songs.

Seven poems by writers of the Harlem Renaissance, translated into German. In Europe, in 19, in the 1920s, Zemlinsky wrote this work in 1929. And it's just gotten its first performance in this concert that you're hearing from Carnegie Hall Live.

Backstage, I'm Jeff Spurgeon, and John Schaefer is here as well.

John Schaefer: Zemlinsky was an interesting character. I mean, there were, as you mentioned earlier, Jeff, a lot of people in German-speaking Middle Europe who were interested in Black American culture. The book that contained all of these Harlem Renaissance poems in translation contained a wide variety of material.

Jeff Spurgeon: And the collection was called Africa Sings.

John Schaefer: Yes.

Jeff Spurgeon: So even the title, might have steered some expectations in directions that we might not think of today.

John Schaefer: Yeah. Lester Lynch back out on stage with Sir Simon Rattle, the two of them bowing to a very enthusiastic audience here at Carnegie Hall.

But to continue the thoughts, Zemlinksy was you know, not the only person to be inspired by these poems and, and this collection. But he was also part of a community, a wide community of composers. Arnold Schoenberg was not only a friend, but eventually his brother-in-law. And he himself, Zemlinksy, was romantically involved with Alma Schindler, who would eventually marry Gustav Mahler. And we have Mahler's Symphony No. 6 coming up in the second half of this concert from Carnegie Hall.

And we are, we are expecting a moment with the soloist, Lester Lynch, joining us here backstage at Carnegie Hall, having worked up a sweat.

Lester Lynch: A little bit. A little bit.

John Schaefer: Were you familiar with the Zemlinsky piece before this?

Lester Lynch: No, I wasn't. In fact I don't think these pieces have been performed much in America, really. And I think you spoke about that earlier. Yeah. And, and certainly that's been my experience that I also was getting to know them. I've, of course, you know, when I was working in Europe quite a bit before COVID, you know, there are a lot of Zemlinsky operas being done in Germany, for instance, in Austria. A bit in Great Britain, but not so much Zemlinsky in this country, you know? And so it's been absolutely wonderful and fascinating to get to know these songs and his relationship with the Harlem Renaissance. I mean, really something.

John Schaefer: And what was it like for you to sing these songs, these most American of poems, auf Deutsch, in German? Is there a little cognitive dissonance happening there?

Lester Lynch: I actually, because I've spent a, fair amount of time in Germany, and I love the language, and I've sung a lot of Schubert and Brahms. In fact, I have a, this is a terrible plug, I have a Brahms recording coming out of the four serious songs. Excuse me for that, everybody.

But but, but, you know, I really do love this language, and, and Lieder, and all that, and of course I've done some Wagner you know, the Rheingold, Wotan. So I, it, it felt right, actually. And it never felt as though it was unfamiliar or was out of place or something like that. It really did feel like we were doing the right thing and like Zemlinsky made the right decisions with these texts and keeping them in German. Yeah.

Jeff Spurgeon: Could you imagine singing them in English? Could you imagine these works being translated with this music and singing the original?

Lester Lynch: Absolutely. Why not? I mean, you know, I, I, I'm for translations. I'm not against that as an artist. So I like singing in original language. And in this case, since the composer chose to, to have the original language be German, I would prefer the German, I must admit. Since it's Zemlinsky, and he was, his sense of the music and the chord structure and all that is for the German text, do you see? And so, if we, if we did it in English, we might lose a little bit of that, that, that play between the orchestra and the text. But I'm not against it, of course.

Jeff Spurgeon: You might gain some broader understanding, too, of what's going on.

Lester Lynch: Well, I, I spent a lot of time reading them in English, in fact. I really searched them out. It was so great to spend time with Langston Hughes again. And tomorrow's, tomorrow's his birthday, right? 125th birthday. Yeah. I do believe. All right. Yeah, yeah, the birth of of, of the great poet.

John Schaefer: Well, it was interesting to hear you say talk about how Zemlinksy made the right choices musically with these texts because the striking thing that we have not heard this piece before, as you say, it's just not done here. But the arabesque, the final song with the, the most provocative of the poems by Frank Smith Horne, you know, you expect, if you, if you read the text, you expect something really dark. And what you get is this kind of sardonic, ironic kind of color.

Lester Lynch: And saying to humankind, basically. You know, this is a moment, this is a poem about hope, that we have this little Irish girl kissing the little Black girl, you know? And yet, there is this thing that we need to deal with over here, there is this issue of racism, you know? And all that. But, we are moving forward, and maybe, you know, again, the children are our future, you know what I mean? Not to quote the song, but here we are, because in fact that's what the song's about, right? It's about these kids, how they don't know racism yet. And yet, there's this horrible thing that's happened, and it's still happening today, you know, maybe not exactly a hanging, but we're still experiencing, you know, racism in this country, of course, but yet, we have many allies and we're moving forward, slowly, but we're moving forward.

Jeff Spurgeon: That is a wonderful, hopeful note, and Lester Lynch, a wonderful thing that you got to do tonight at Carnegie Hall.

Lester Lynch: Thank you, such a pleasure. Thank you so much.

Jeff Spurgeon: Thank you for spending some time with us. Baritone Lester Lynch, soloist in the Zemlinsky Symphonic Songs tonight in this broadcast by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra from Carnegie Hall Live.

We have a couple of the players here. We're at intermission now but the players need a little time because they've got a big lift in the second half of this program. Just another little Mahler symphony, but here with us are Natalie Schwaabe, who plays flute and piccolo, and Korbinian Altenberger, who is first principal of the second violins in the Bavarian Radio Symphony.

So, have you guys played much Zemlinsky? Were these works things that you knew that we just heard?

Korbinian Altenberger: Actually, so far we haven't played much Zemlinsky in the recent years. I mean, a couple years ago I played his symphony, the Lyric Symphony, which was a great experience, and we're actually going to play it next season again, which I'm really looking forward to.

Jeff Spurgeon: And so tell us a little about the Mahler. What do you look forward to in in the Mahler 6?

Korbinian Altenberger: Well, it's an incredible piece because it's so different from the symphonies he has written up to this point. And he introduces this new thing in the fourth movement, a sledgehammer, which is very spectacular.

Jeff Spurgeon: You get to, you're not far away from it either in the second violins, are you?

Korbinian Altenberger: Pretty much as far away as you possibly could be.

Jeff Spurgeon: Oh, on the other side, okay.

Korbinian Altenberger: I mean, Natalie's much closer, so.

Natalie Schwaabe: He's very fortunate not to be, to be very far away. It's always quite moving.

Jeff Spurgeon: You must brace yourself for that, when those moments come.

Natalie Schwaabe: In a way you do. I mean, the whole, that last movement is just gigantic. It never sort of ends. You turn a page and you think, Oh, we're nearing the end. Oh, not at all. And then comes this hammer, so. But if it's spot on, it's amazing, and it doesn't actually hurt. It was, I think, two concerts back. It was just perfectly timed, and then it's, it's a revelation.

John Schaefer: With Mahler symphonies, there's so much going on, it seems that this is, this is where a conductor can make a big difference, and when you're performing a sprawling piece like that with Sir Simon Rattle, how different is the experience working with him as opposed to other conductors the orchestra has performed with.

Natalie Schwaabe: Well, I'd say, I mean, we usually perform Mahler with very, very good conductors, so we're, and I always find it incredible how they manage to keep that tension going for such a long time, and to keep that build-up, and Simon Rattle is no different than to any other amazing conductor we've done them before.

I always find it very exciting because he doesn't do, one night is never the same as the other. It's always a new journey we're, we're pursuing, which makes it, we sort of sit on our seats edge and that's, that's the magic of it as well.

John Schaefer: Right.

Natalie Schwaabe: It just makes you bond even more together and makes it a very exciting journey.

John Schaefer: And, and gets you out of your comfort zone. Oh yeah, here's Mahler Six again.

Natalie Schwaabe: Well, well I never think Mahler Six or any Mahler symphony is a comfort zone to be honest. I always find it incredibly inspiring to play but, or do you find it in your comfort zone, Korbi?

Korbinian Altenberger: Well, I mean, it's unbelievable to perform this piece with Simon Rattle because he really manages to get this art, like, from the very first to the very last note. And it's a very special experience, especially here at Carnegie, to perform this piece.

Jeff Spurgeon: Have you played at Carnegie Hall before?

Korbinian Altenberger: A couple times. I used to live in the States for a long time. So, I actually went to college here, so I've been here before.

Jeff Spurgeon: So this is comfortable for you. And what about you, Natalie?

Natalie Schwaabe: Well, it's quite touching. My first tour with the orchestra was here in Carnegie in '96 with Lorin Maazel.

John Schaefer: Wow.

Natalie Schwaabe: So it feels in a way like coming home. And I always find it incredibly moving, because you know Mahler conducted here, and all the great amazing musicians conducted here, so it just feels like we continue that tradition.

Jeff Spurgeon: And what is it, how is the feel for the orchestral sound on stage at Carnegie?

Natalie Schwaabe: Well, for us woodwind players, it's very different, because we're used to being seated slightly elevated to the string players. But we actually, for the feeling that you're down in the dumps, it's a different feeling, but you can actually hear really well, and it merges incredibly well. So it's actually a lovely feeling, but it's different.

Jeff Spurgeon: And, and what is it like for the string players?

Korbinian Altenberger: For the strings, I mean, it's, it's a great hall to play in, and we have played this piece in many halls that weren't as amazing. And so when we're here, it's also like it's, I mean, it's always a special, special feeling to go on stage here because of the history of the hall and everything. So for us, it's, it's just a pleasure to be here.

John Schaefer: I had a final question for the two of you, since you have both been here before, when you're in New York and you have a little free time, where do you like to go? What do you like to do?

Korbinian Altenberger: I love to go to the Frick Collection.

John Schaefer: Frick Collection, very good.

Natalie Schwaabe: I love the Frick Collection as well. What I also really love is the Cloisters out in the north of Manhattan. And that's something so unique, you wouldn't be expecting to find French monasteries there at all.

Jeff Spurgeon: Not on the north side of New York City, that's for sure.

Well, thank you both so much. You have a little thinking to do, I'm sure, before we you take us all with you on this great Mahler journey.

Natalie Schwaabe and Korbinian Altenberger, members of the Bavarian Radio Symphony, thank you so much for spending a few minutes with us here on Carnegie Hall Live.

Classical New York is 105. 9 FM at HD, WQXR Newark, and 90. 3 FM WQXW Ossining.

This concert by the Bavarian Radio Symphony continues in 15 minutes or so. Intermission really is just underway. A little bit of stage resetting has to be done. And then we're going to take a great journey in music of Gustav Mahler with his Sixth Symphony.

John Schaefer: But a little bit of music history now. On November 8th, 2019, we were here in Carnegie Hall for a live broadcast with this orchestra, the Bavarian Radio Symphony, in what turned out to be conductor Mariss Janssen's last concert. Here is a recording from that night, a little bit of the Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor.

MUSIC: EXCERPT FROM BRAHMS SYMPHONY NO. 4 IN E MINOR

John Schaefer: Some music by Brahms from his Symphony No. 4 in E minor as it was broadcast on this Carnegie Hall Live series back on November 8, 2019, with tonight's orchestra, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted for the final time by their longtime music director, Mariss Jansons, who died just a few weeks later on December 1st of that year.

Jeff Spurgeon: We are in intermission of this concert by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. You heard a couple of the members talking about enjoying being on stage here at Carnegie Hall. So many great moments in American musical history have happened here, and now there's a new podcast that tells the stories of some of those incredible events.

The new podcast hosted by Broadway star Jessica Vosk is called If This Hall Could Talk. Each episode centers on a single object in the Carnegie Hall Rose Archives that represents an iconic moment in Carnegie history. The first episode is about an album cover, autographed by Judy Garland, and tells the story of her 1961 debut. One of the great legendary events in Carnegie Hall history.

The podcast is called If This Hall Could Talk. It is available wherever you get podcasts and we have a little more about the series here.

Jessica Vosk: Carnegie Hall. It's one of the most famous concert venues in the world.

"The first time I walked on the stage, I felt like my feet were moving, but they were not touching the floor."

I'm Jessica Vosk, and I'm thrilled to be hosting the new podcast, If This Hall Could Talk. Each episode features a unique item from Carnegie Hall's Rose Archives, like Benny Goodman's clarinet or Ella Fitzgerald's glasses.

"The variety is unique, so it becomes this kaleidoscope of music. of our history."

Come with us as we travel back in time to explore how that past shaped the culture we live in today.

If This Hall Could Talk, produced by Carnegie Hall and Sound Made Public and distributed by WQXR, is available now wherever you get podcasts.

John Schaefer: Well we're nearing the end of intermission here at Carnegie Hall and there is one more piece and it's a big one from the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Gustav Mahler's Sixth Symphony. It's a work that contains some unusual sounds, cowbells, and a giant, devastating hammer blow.

The order of movements has been a bit of a puzzle, apparently even for Mahler himself, and while he wrote it during a happy time in his life, this symphony is about as dark as anything in the entire repertoire. The work has the nickname "Tragic" applied to it, not by Mahler, but the conductor Bruno Walter claimed Mahler had used the word in describing the piece. Sir Simon Rattle, who will conduct this performance, told us that that big, dark, brooding movement that ends the piece is so powerful precisely because it isn't in the forecast.

Sir Simon Rattle: What people forget is that in this gigantic finale, so far in music the biggest finale written, about 35 minutes, that A major nearly wins. It is a titanic life struggle of what will happen and this is why it is all the more devastating because until, oh, two minutes before the end, A major is about to burst out and the cutting off of that is so devastating that I can understand why, even compositionally, Mahler didn't need the third hammer blow, because in a way, simply the music has done it for him.

Jeff Spurgeon: The hammer blow is one of the most defining features of this work, and challenged to meet Mahler's description of the sound that he wanted. Orchestras have built all kinds of drum contraptions to make this special effect. Sir Simon says that orchestras have to join Mahler in pushing the boundaries of this particular musical expression.

Sir Simon Rattle: What was he imagining for the hammer? I mean, psychologically, it's very clear what a crushing blow it is but we've all found our ways to do it, and it's a kind of, it's a theatrical gesture. which almost doesn't belong in the concert hall. It's as though it's exploding the concert hall as well.

John Schaefer: Once again, Sir Simon Rattle talking about these, the famous hammer blows. There are two of them in the score. Originally there were five and then Mahler reduced them to three. There has also been controversy over the order of the two middle movements. Mahler himself seems to have been unsure of which way he wanted it to go, and Simon Rattle says that makes perfect sense when you remember that Mahler was both a composer and a conductor.

Sir Simon Rattle: There is this wonderful fight over what order the middle movements go in, and I can see probably it's the composer who originally wrote the scherzo second, and it's the performing conductor. who realized that dramatically the two movements were so similar that put the scherzo third. This is part of what Mahler is going through.

Jeff Spurgeon: And so we experience Mahler in both ways in this work as a conductor and a composer because of that change in the work. Sir Simon Rattle also told us that there are moments in the score where as a conductor you're thinking I can push things along a little bit and at that very moment there's a note in the score by Mahler that says, stay calm, keep the tempo steady. So one of the things Sir Simon Rattle the words he used, he said it's, it's a Janus-like juxtaposition. You have both the showman, the conductor leading, and you have the creator mind, both in a single man in, in all of these works, obviously. But it is a special connection for a conductor to do these pieces because of course Mahler himself was on the podium.

John Schaefer: And having mentioned the hammer blows, we should probably describe how this orchestra, this evening, has decided to go with that, which is they've got a big wooden box, it is elevated so it will resonate. Have you seen the mallet?

Jeff Spurgeon: The mallet is, the mallet is the fun part. It looks like a cartoon mallet. Somebody would chase somebody in a cartoon with that mallet.

John Schaefer: It's a Bluto from Popeye. It's a Bluto hammer. You know, you would need somebody with, you know, like rippling muscles to pick this thing up and hit the box with it. So good thing that Mahler cut the five original blows down to two or there could be some muscle strains in the percussionist's future.

Jeff Spurgeon: And you'll also hear some sounds of the outdoors, and of nature, and of the farm agricultural community. There's a great chorus of cowbells, and there's a string of about eight of them sitting, oh, 10 or 15 feet away from where John and I are backstage right now. So those effects will be part of this journey to this sixth symphony of Mahler, which takes this dark turn at the end. And Mahler is so full of affirmation. in his earlier symphonies. And then this one goes, goes to the dark side. And it was a happy time in Mahler's life. So what do we say about that? That we have a man here who was able to channel things that he was not feeling in that moment. Just incredible creative power.

John Schaefer: Well, and we have heard a fair amount of Mahler in this season of Carnegie Hall Live, and we've discussed this in the past, that he was an early adopter of psychotherapy. Yep. And you know, that probably had something to do with the channeling of the feelings that you hear in these mid to late symphonies.

Jeff Spurgeon: And so we are getting ready now to take this great journey of the Sixth Symphony of Gustav Mahler with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and their new Chief Music Director and Chief Conductor, Sir Simon Rattle. The Sixth Symphony of Mahler comes to you now from Carnegie Hall Live.

MUSIC: MAHLER SYMPHONY NO. 6

John Schaefer: From Carnegie Hall, Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 6. played by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Simon Rattle. A musical journey nearly 90 minutes in length, ostensibly in A minor, although it is a journey, and it wanders from key to key throughout the course of its four movements, and rapturously received by the audience here at Carnegie Hall, as Sir Simon Rattle exits the stage, leaving on stage the members of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra to momentarily bask in the applause of the Carnegie Hall audience.

An extraordinary piece, the last movement is a symphony unto itself.

Jeff Spurgeon: One of the longest of its kind, some 35 minutes in length, and as you said John, an absolute journey. And now returning to the stage, Sir Simon Rattle, the audience here at Carnegie Hall on its feet. Many of the orchestra members paying their own tribute to their new chief conductor.

He shakes hands with the concertmaster, various members of the string sections, and at the end of the piece he, he gave a gentle, quiet nod to the orchestra as he has done at the conclusion of all the works on this program tonight, just saying, done a good job. And as he walked off the stage just a moment ago, he looked over at the percussion section and put his hand to his heart. An appreciation of their work.

And now all of them on stage, all of them standing I should say, Sir Simon and the orchestra.

John Schaefer: And mentioning the percussion section, they weren't all on stage. There was one percussionist standing right where we are seated here backstage with a set of cowbells and tubular bells and those could be heard coming from off stage at key moments in the second and fourth movements of the symphony.

On the other side of the stage wall from us is where the hammer is, the so-called Mahler hammer, which is supposed to provide a kind of thud, you know, the hammer blow of fate. And when that first, when that first hammer hit, we felt it.

Jeff Spurgeon: Yeah, you felt it. We felt it in our bodies, even through the walls of the stage.

Another curtain call. And Sir Simon asks the trombone section to stand.

John Schaefer: By miming playing a trombone, which I don't think I've seen before.

Jeff Spurgeon: And they did have that climactic moment at the end, that trombone choir that just announces the inevitability of the conclusion of this work.

John Schaefer: Once again, the Mahler Symphony No. 6 has been nicknamed The Tragic. That was not Mahler's nickname for it, although it seems like he described it that way to fellow conductor Bruno Walter at one point, and that seems to have given license to people to apply that nickname to the Symphony No. 6. But that's just one of many questions that this symphony raises.

There are two celestas on stage, not for the reason Mahler wanted. Mahler wanted two or even three celestas, but it's usually performed on one. But there's a reason why they had two in the orchestra.

Jeff Spurgeon: There was some dissatisfaction with the sound of one of the celestas, and so another one was ordered in and brought in.

So the celesta player played the top octave on one instrument and the bottom octaves on another instrument, in order to get the sound that they wanted for this particular performance. So, yes, Mahler did get two celestas, but not two celestas. One and two for this particular performance.

John Schaefer: There are also two harps included in the orchestra, despite the fact that the score seems to call for four at one point. And, you know, it's just, it's, it's a question, it's a symphony that seems to raise more questions than it answers, which can be a wonderful thing in any creative endeavor.

Jeff Spurgeon: Absolutely, and we take, again, it's another way to take the journey. And as Sir Simon told us, as we related earlier, as a composer, Mahler thought that scherzo should come first. As a conductor, he said it should come after the second movement.

John Schaefer: Right.

Jeff Spurgeon: And, and so, and in fact, there were five hammer blows in the original score. Knocked down to three, and now two are played. Sir Simon told us in a segment we did not share with you that one time he added the third hammer blow in a performance, but the percussionist got lost, and so the third hammer blow was never sounded, and Sir Simon said, I took that as perhaps a cosmic cue that that was not something that should be attempted again.

John Schaefer: Although there are musicologists who claim that the third hammer blow should be reinstated, just as there are people on both sides of the divide, which is the second movement and which is the third.

Jeff Spurgeon: And so it is one of the great magical parts of this symphony that you can go back to it again and again and look at these fresh approaches and always so much life in the performance. And as Sir Simon walked out, he turned to the orchestra members, who you hear filing off stage in front of us. He turned and said, wow, you guys, to the orchestra. And we would say that too about this performance tonight, which included not only the Mahler Symphony No. 6, but Paul Hindemith's Ragtime, a jazzy concert opener. And, the first time ever on the Carnegie Hall stage, the performance of Alexander Zemlinsky's Symphonic Songs, settings of Harlem Renaissance writers in German, sung by baritone Lester Lynch.

John Schaefer: Fun fact, Zemlinsky was also invited by Mahler to do a two-piano arrangement of the Symphony No. 6. I cannot imagine a more thankless task.

But we do have people to thank. Clive Gillinson and the staff of Carnegie Hall and WQXR's team includes engineers Edward Haber, George Wellington, Duke Marcos, Noriko Okabe, and Chase Culpon. Our production team, Eileen Delahunty, Max Fine, Aimée Buchanan, Yueqing Guo, and Christine Herskovits. I'm John Schaefer.

Jeff Spurgeon: And I'm Jeff Spurgeon. Carnegie Hall Live is a co-production of Carnegie Hall and WQXR in New York.