Gino Francesconi: Maya Angelou was talking with Sammy Davis in 1960. I don't exactly remember where they were, and they said, "Between the two of us, how many artists do you think we could get together to do a benefit for Martin Luther King and his Christian—Southern Christian Leadership Conference?"

Jessica Vosk: Gino Francesconi, founder of the archives at Carnegie Hall.

Gino Francesconi: And Maya Angelou said, "I can get Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier and maybe Count Basie." And Sammy Davis said, "I know who I can get."

RECORDING OF “I CAN’T BELIEVE YOU’RE IN LOVE WITH ME”, PERFORMED BY DEAN MARTIN.

Will Friedwald: Oh, yeah! This was a huge deal…

Jessica Vosk: Will Friedwald, author of dozens of articles and books on popular music including Sinatra: The Song Is You.

Will Friedwald: This was an event you could actually buy a ticket to, so that was a really, really big deal.

Gino Francesconi: And they were constantly adding to this event—Carmen McRae and Joe Williams and Tony Bennett—and the list kept growing, and the demand for tickets kept growing…

Will Friedwald: They're not just massive names, but it’s safe to say that just about any of these names could have filled Carnegie all by himself.

Jonathan Eig: I think you can make the argument that cultural figures, entertainers, and athletes paved the way for King.

Jessica Vosk: Historian and author of the Martin Luther King, Jr. biography King, Jonathan Eig.

Jonathan Eig: And, you know, really, it's like, just like today when, you know, a celebrity, when Taylor Swift makes a political statement right now, when she comes out against a candidate for office in her home state because that candidate opposes reproductive rights.

That has a huge impact on people who did not necessarily think about politics before, because everything she says matters to her fans. And Sinatra was the Taylor Swift of his day.

RECORDING OF “SWEETY CAKES” PERFORMED BY THE COUNT BASIE ORCHESTRA.

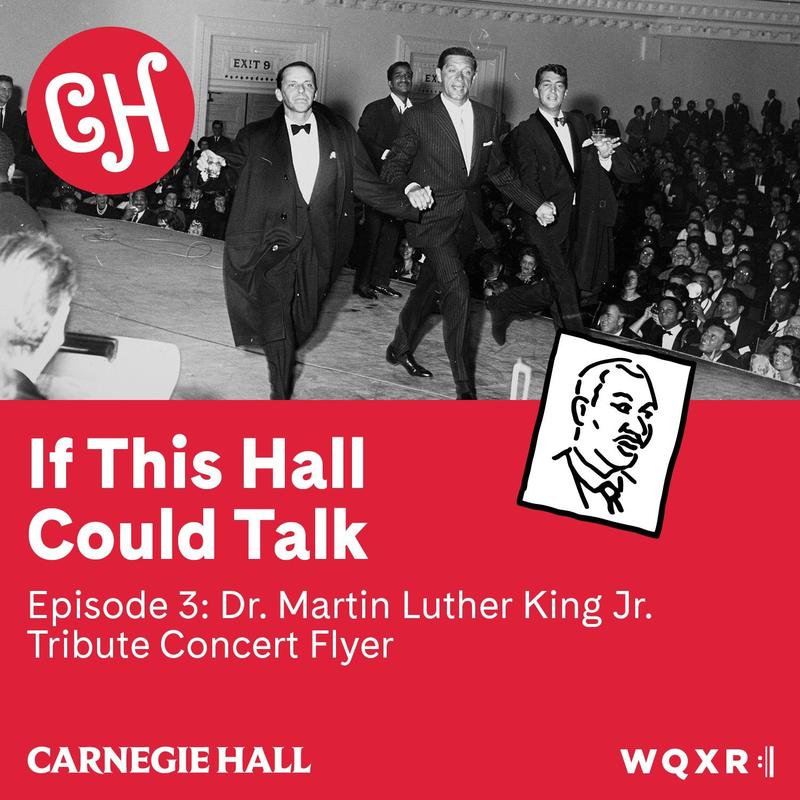

Jessica Vosk: Welcome to If This Hall Could Talk, a podcast from Carnegie Hall. I am your host, Jessica Vosk and in this series we’ll look at the legendary and sometimes quirky history of the Hall. From momentous occasions to the eclectic array of world-renowned artists that have taken to the Hall’s stages, in each episode, we’ll explore unique items from our archives collection and travel back in time to relive incredible moments that have shaped the culture we live in today.

In this episode, we’re taking you back to 1961, a seminal moment in the history of the US where change, or at the very least, the hope for it, was afoot.

RECORDING OF AN ARCHIVAL NEWSREEL FROM 1961 DETAILING ALL OF THE HISTORICAL EVENTS OF THE YEAR.

Kennedy had just been elected, John Glenn orbited the earth and the first black student, James Meredith, attended the all white University of Mississippi. The civil rights movement was gaining traction and it needed support.

Continuing with Andrew Carnegie’s aspiration that (quote) “All good causes may here find a platform,” Carnegie Hall hosted a tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr. and a benefit for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The object of inspiration for this episode is the ticket stub for that event which was star studded. It seemed that everyone was there.

Sammy Davis Jr., Frank Sinatra, Mahalia Jackson, Toni Morrison and countless others who performed in support of Martin Luther King, Jr. and all that he stood for: To use nonviolent protest as a means to increase awareness and reform.

And the amazing thing: They all performed for free.

Rob Hudson: Dr. King, his fight had been going on for a long time,

Jessica Vosk: Archivist Rob Hudson.

Rob Hudson:…and African Americans were well aware of what he was doing.

Emilie Raymond: January 1961,

Jessica Vosk: Emilie Raymond is a history professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and she specializes in 20th century American political culture.

Emilie Raymond: it was an interesting time for the civil rights movement, and for celebrity involvement in the civil rights movement, and also for the nation, because John F. Kennedy had also just been elected and inaugurated into the presidency.

RECORDING OF THE INAUGURATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY AS PRESIDENT IN 1961.

RECORDING OF “IT’S JUST ONE OF THOSE THINGS” PERFORMED BY CARMEN MCCRAE.

Emilie Raymond: It's hard for us now to think that Martin Luther King, Jr. wasn't always popular and successful. [laughs], but that wasn't the case. The SCLC was very small. It only had three full-time employees.

King was still struggling in many ways.

Jessica Vosk: Again, Jonathan Eig.

Jonathan Eig: I think he was kind of in a quandary at that time, and he was also trying to figure out how the SCLC was going to fit into American society.

Emilie Raymond: Its strategic leadership, you know, were his friends and other ministers who were mostly in Southern churches.

Jonathan Eig: Some people were suggesting that it should become a membership organization, and that might compete with the NAACP. It was hard for him to really find traction. It was hard for him to figure out how to take his public image, his great fame, his power, his—and leverage that into a movement. The movement really was still struggling, and I think that's why he really had to raise money almost entirely on his own because they were not a membership organization.

Emilie Raymond: And so what they were looking to do was to try to increase their budget to have a more professional national permanent organization that could kind of rise beyond their last success, which was the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 and 1956.

RECORDING OF MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. SPEAKING TO CROWDS ABOUT THE MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT

Jessica Vosk: It seemed like every important performer of the time joined the bill that night, and headlining it all was Frank Sinatra, who was at his prime.

RECORDING OF THE THE SONG “I’VE GOT THE WORLD ON A STRING” PERFORMED BY FRANK SINATRA.

Will Friedwald: We go back, and of course everybody knows who Martin Luther King is. We all grew up with Martin Luther King.

Jessica Vosk: Will Friedwald.

Will Friedwald: But it’s interesting, when you read the press clippings from the period, you get the impression that most people, especially most white people in America, by 1961, they had never heard of him! He was a brand-new name to them. Unless they had happened to follow the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the Spring of 1956. But that was not necessarily something that everybody all over the country or New York was necessarily paying attention to. When you read about this concert in the clippings at the time, they make a point to tell you who Dr. Martin Luther King is, as if he’s a new name to them, which I think is fascinating.

Rob Hudson: To broaden this in the consciousness of the rest, you know, like, white America, needed to happen. And, so, to have somebody like Frank Sinatra step forward, and, you know, Frank Sinatra was always…He could not stand, you know, hatred, division, prejudice, you know, anti-Semitism. He was always standing up for these things. He was very close to Sammy Davis Jr.. It was—he was just one of his closest friends, and …I’m sure there probably wasn't a moment's hesitation from Frank Sinatra to do this.

Jessica Vosk: Looking at the flyer for the event, classical singer and creator Davóne Tines reflects.

Davóne Tines One of the most striking things about the event in 1961 is one of the flyers that has the Rat Pack and Frank Sinatra on it, their heads as cutouts, interspersed within the text, and then a little picture of Martin Luther King there as well, outlined in white, so it's very present.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “I CAN’T BELIEVE YOU’RE IN LOVE WITH ME” PERFORMED BY DEAN MARTIN.

Davóne Tines Visually what you get from that is out of five performers, four of them being white, and they are there in reference to this one Black man to show support or connection.

So that flyer means a lot because it's predominantly white performers that were headlining, quote, unquote, that event to an audience that is largely white, you know, the people that venerate Carnegie Hall, aside from the larger groups of people that would be drawn there because of their favorite performers. But I was like, wow, that's back in the '60s, but I think that that's doing it right. I think that that's saying, you know, the leading white performers speaking to the larger majority, being the conduit for saying this Black man, Martin Luther King, and his work is something you need to be engaging.

Jessica Vosk: This is how it happened.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “PLEASE DON’T TALK ABOUT ME WHEN I’M GONE” PERFORMED BY SAMMY DAVIS, JR.

Emilie Raymond: Sammy Davis Jr. was proving himself a really successful fundraiser for civil rights organizations. Davis went to the rest of the Rat Pack, supposedly, in the steam room at the Sands, which is where they were all staying while they were doing their nightclub act and in making the movie Ocean's 11.

Will Friedwald: Sinatra was a part-owner of the Sands, in Las Vegas.

Emilie Raymond: And they all said yes. The steam room is like where they spent a lot of time, you know, between their acts and their filming and so forth. So, yeah, there's billowing steam, there's white towels, there's their normal hijinks, and then there's the, "Yeah, we'll do this benefit." [laughs]

Jessica Vosk: What was so special about this event was that it wasn’t just musical performers—Count Basie, Tony Bennett, Harry Belafonte, Dean Martin, but also others, like boxer Joe Williams and actor Sidney Poitier.

Emilie Raymond: Davis started planning kind of the entertainment side of it, the program. And then, in the meantime, Harry Belafonte, who was also very invested in the movement, and Maya Angelou worked as sort of the co-chairs on the more logistical elements of, you know, securing Carnegie Hall, getting sponsors, getting ads in the paper, putting the program together, all those sorts of things.

Rob Hudson:: To me, it just kind of is so representative of the zeitgeist too. When you look at the performers that were on the stage, some of the others that we didn't talk about. There was a dance team named Augie and Margo. It was Augie and Margo Rodriguez, husband and wife dance team, and they did more than anybody else to popularize the mambo. So, they were there. Nipsey Russell was one of the hosts.

Jessica Vosk: You’re listening to If This Hall Could Talk. I’m Jessica Vosk. We’ll return to the show in just a moment. Stay with us.

AD BREAK

Jessica Vosk: Welcome back. Let’s get back to our conversation about the tribute concert for Martin Luther King Jr. held at Carnegie Hall in 1961.

Emilie Raymond: It seems like there was so much anticipation and excitement about it. And you could get in—they sold tickets at a whole variety of price points, you know, so you could get in somewhat cheaply, I think, for as little as $5. But they also sold box seats and, you know, you could buy out a box seat. And so some of—some people were buying tickets for like $800, and so people were very dressed up. There was an [laughs] element of glamor to the whole affair. It was sold out and beyond capacity, so they were actually putting chairs up on the stage.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “MR. BOJANGLES” PERFORMED BY SAMMY DAVIS, JR.

Gino Francesconi: And it went on all night. I think it went—

Rob Hudson: It was like four hours or more.

Gino Francesconi: At least.

RRob Hudson: Over four hours.

Gino Francesconi: Right. Overtime at Carnegie Hall was always 6 minutes after 11. So, it went way, it went way past that. And, you know, it was just they were having so much fun. Why stop, you know? And what happens with a lot of benefits that the cause is so sincere and so genuine that because so many people volunteered their time, they want to give everybody their five minutes on stage.

And, so, the night just goes on and on, you know…It was a really extraordinary, extraordinary event.

Jessica Vosk: Again Davóne Tines.

Davóne Tines The magic of performing arts is that you create a reality for people to exist within, and you have the amazing opportunity to make a world that looks like the world you want to be reflected outside of the theater.

You know, they're able to, one way of saying it is, vouch for but also invite and say, "You love me, Frank Sinatra. And you know what I love and appreciate? The work of this man." And I think that is a very clear conduit to get a larger audience that would never entertain Martin Luther King to actually walk through the doors, and think about it.

Jessica Vosk: And the deep friendship and camaraderie between Sammy Davis Jr and Frank Sinatra was undeniable.

Tom Santopietro: When Sammy Davis Jr., I think he was 12 at the time, you know, he was already performing. He had been performing since the time he was a toddler with that Will Mastin Trio.

Emilie Raymond: Sammy Davis Jr., he had grown up as—in a vaudeville act, and he was just a show business person from like the age of three years old, you know. And so he was always climbing, and always trying to be a bigger star, and always striving.

He was a great tap dancer, doing a lot of tap dancing, and just sort of joshing around on the—on the stage. So it was really revolutionary, especially because one of his big shticks was he was a great mimic. So he did these impersonations of all kinds of people…

RECORDING OF THE SONG “GOT A GREAT BIG SHOVEL” PERFORMED BY SAMMY DAVIS, JR.

Emilie Raymond: …but including white people and like people like Jerry Lewis and Frank Sinatra. And his father, Davis's father, was concerned that this would be too controversial, and this would get them, you know, lynched, you know, or some sort of terrible reprisal. But it didn't, and people seemed to really get a kick out of it. And so on one hand, he had this very, I think, daring persona from the standpoint that he was taking risks and doing things that other people hadn't done.

Tom Santopietro: And Sammy idolized Frank, and he met him briefly when he was 12 years old, and thought this was incredible. And then I think it was 1945 right, you know, when the war was ending, Sammy was I think then 16, and he was invited into Frank's dressing room. And Frank recognized the incredible talent that Sammy Davis Jr. was. And, so, when Frank was playing the Capitol Theatre, he said to the bookers at the Capitol Theatre, "I want to use Sammy Davis Jr. and the Will Mastin Trio." And they said, "Oh, nobody knows who he is." And Frank Sinatra said, "I want them, and I want them to be paid $1,200 a week," which was quadruple what he had ever made before, what Sammy Davis Jr. had ever made before..

Will Friedwald: Which is really amazing, that Sinatra was able to do that, and to find—to see this young guy, who was still part of the trio, and say, “This is a talent, and this is somebody I want to pay attention to. This is somebody I want to be part of my life.” So, they go way back.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “THE BIRTH OF THE BLUES” PERFORMED BY SAMMY DAVIS, JR.

Jonathan Eig: I do know that Davis was definitely one of the, you know, top four or five celebrities that King felt he could count on, and because he had access to the, you know, Sinatra.

And, you know, I think each of them, Belafonte had certain people he was connected to, and Davis had some others who he was better connected to. But, you know, they—I think they served in similar roles and that King knew he could call on Sammy Davis, not just to show up but to get others to show up.

Tom Santopietro: And what Frank Sinatra would do is Sammy Davis Jr. would be on stage, and Frank Sinatra would go out on stage, and put his arm around Sammy Davis Jr. It was like a big brother gesture, but it spoke powerfully to the—how he felt about Sammy Davis Jr. And, look, the relationship fit both men very well because Frank loved the adulation from Sammy, and Sammy needed a big brother quasi father figure at the same time. So, it really worked well for both of them and, of course, each knew the other one was a giant talent.

Jessica Vosk: There were several events that Sammy Davis Jr. had done that made King think this one at Carnegie could be a great success.

Emilie Raymond: He worked for the NAACP in 1957 on a big fundraiser, and then he chaired a Life Membership Campaign for their Freedom Fund, which had been pretty successful, and he had gone to some mass rallies and so forth, and then—but the big moment came when the Urban League of Chicago asked him to participate in this Jazz Fest. And this was in 1960, in the summer or fall of 1960. And it was just as the Rat Pack was making its big splash with Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop. So he said he would go to this event, and then he invited—and they said yes—Sinatra and Lawford to come with him. And it turned into this huge success where they had to add extra seats and extra microphones, you know, all this stuff to make it—to make it good [laughs], like, a good actual performance.

And so just a few weeks after that, that's when King asked Davis to do this big tribute. So I think the success of that Urban League Jazz Fest is what led them to ask him.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “CORNER POCKET” PERFORMED BY THE COUNT BASIE ORCHESTRA.

Jessica Vosk: In 1961, when the tribute to and fundraiser for Martin Luther King, Jr. happened at Carnegie Hall, hope and change was in the air. And it was such a special moment for Sinatra.

Will Friedwald: In January 1961, Sinatra is on this incredible career high. And on January 19th, ’61, he produces the Inaugural—the greatest Inaugural in the history if inaugural galas—for President Kennedy. And the fact that he is asked to produce this was probably—I think it’s safe to say, the fact that Sinatra always had an interest in politics, he always had an interest in these issues—the fact that he was called upon to produce this gala I would say was probably the high point of his entire life. Not just up until that point, but maybe ever going forward.

RECORDING OF JOHN F. KENNEDY SPEAKING AT HIS INAUGURAL BALL IN 1961.

Will Friedwald: But really I would say this moment, when Sinatra does that Gala, and then follows it eight days later with his first really big concert at Carnegie, that really is an all-time career high for him.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “NEW YORK, NEW YORK” PERFORMED BY FRANK SINATRA.

Will Friedwald: It feels like this is an era of new possibility. The fact that we have—the youngest president ever, is in office…It was kind of this age when that generation was going to step in and take over, and there were fresh possibilities. This idea that we could finally do something about segregation. All these people that grew up with segregation, for generations people just took it for granted.

Tom Santopietro: …and Frank Sinatra is sending a message of not only performing, of course, alongside all equals, African-American performers, but also saying this cause, Dr. King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, is a cause that is important to all Americans because it's about the equality that is supposedly written into our most important documents. And I think, in that way, the message came home to a lot of people that might not have paid any attention at all otherwise.

Will Friedwald: …And it should be said that this is years and years before—probably in the late 1960s, a lot of actors started taking a stand against the Vietnam War and in favor of racial equality, but Sinatra is way ahead of that by at least a generation.

Emilie Raymond: So this was a real turning point for the SCLC. This benefit allowed them to hire three additional employees. One of the people they hired was—his job was to be a professional fundraiser for the organization. It was the first one they'd had, and he was really effective. And he recognized that this event helped make King a celebrity in his own right.

Emilie Raymond: He was becoming more and more nationally known, but that kind of helped put him in a more star-studded position, I think. So he used the celebrity that King gained from this event to push their fundraising even further. So it seemed like a big turning point, to me, for the SCLC. And other civil rights organizations sort of took note, and started doing more and more of these as well. And I'll say the Rat Pack did two more after this that were almost as successful.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “Go Tell it on the Mountain” PERFORMED BY MAHALIA JACKSON.

Jessica Vosk: The ticket stub is just one of the many artifacts from this benefit. Although the concert itself was never recorded, there were numerous photos taken that evening. Again, Rob Hudson.

Rob Hudson:…there was one that really grabs me every time I see it. And it's this photo of Frank Sinatra, and he must've just finished singing a song. And he's standing there. You can see he's kind of got the microphone in his right hand, sort of down by his side. And he just has this look on his face. It's just like he looks probably the happiest he's ever looked in his life, to me, you know, because he's just—he's got this smile, and it's just like love and joy that he's radiating. And you can tell he's probably reacting to applause. I think it's such a wonderful moment.

And interestingly enough, …

Jessica Vosk: Who, by the way, was married to John F. Kennedy's sister…

Emilie Raymond:…and Joey Bishop, they were stranded, and they couldn't even make it at the last minute. So they got two other television comedians to kind of go on with them. But the thing about those Rat Pack shows that I think people really liked was that it was a rehearsed act to a certain degree, but it also seemed very, very loose and very spontaneous.

And it seemed like they were just more clowning around as usual as opposed to putting on a rehearsed show. And it was really clear that they were all friends. So to have this kind of interracial group who were clearly so intimate as friends, and spent a lot of time together off stage was important for the movement.

Jonathan Eig: I think that King recognized that these figures had, like he did, an ability to transcend their Black audiences, to go beyond, and that was King's superpower too. He absolutely knew how to work a Black crowd, and Black audiences responded to him, you know, really emotionally. But white audiences heard his message, and responded to it too.

Emilie Raymond: In the case of the civil rights movement, it was really important because the celebrities that were—that were most effective were part of the constituency. I mean, they weren't hired spokespersons. They were people who had lived what the movement was talking about, could—and would benefit by the successes of the bene…of the movement too. So they had a real strong personal interest in it. So that was important. Then they could articulate what the movement was about. They had the ear of larger audiences than the movement often did, because of their fan base.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “CORNER POCKET” PERFORMED BY THE COUNT BASIE ORCHESTRA.

Davóne Tines You can get somebody, you know, politically informed or riled up or for all the things that you can outline about, you know, the [laughs] troubles of the world, and how we're trying to deal with them, the emotional appeal will always work best, and the arts have the greatest capacity and potential for making an emotional appeal. You know, we deal in storytelling, we deal in how you get people to engage things that they otherwise wouldn't have a space to do so.

So, in fact, the arts are critical in saying, I can help make you feel this so that you can do something about what you feel.

Emilie Raymond: The fact that not only could you get people to come but they would pay to come [laughs], that's pretty exciting, so—and they got to see a lot of entertainment. The whole show, I think it was like three and a half hours altogether. It was really long. And so if you went, you got an earful and sightful. [laughs]

Jonathan Eig: White Americans were willing to listen to them and reconsider some of their racist views because there were these figures who they admired for their, their talent as an actor, as a singer, as an athlete. And it kind of shook them in a way.

Davóne Tines I don't know if today you put on a Martin Luther King tribute concert, and it was predominantly white performers, you might get—you would definitely get backlash, and it might be misdirected backlash by saying like, he's a Black figure and this needs to represent Black people. But it's like, okay, if we're in the mode of talking about change, then we have to speak to the majority where the power lies that be.

And those are the people that this needs to be directed at. And I think the easiest conduit towards that is people that look like them. That's the potential for truer allyship. So it's amazing that that was happening in intentional and unintentional ways in the '60s, and I hope we continue to learn from that.

RECORDING OF THE SONG “NEW YORK, NEW YORK” PERFORMED BY FRANK SINATRA.

Jessica Vosk: Many thanks to Clive Gillinson and the dedicated staff of Carnegie Hall. As well as guests Jonathan Eich, Tom Santopietro, Emily Raymond. Devon Tynes and Will Friedwald.

If This Hall Could Talk is produced by Sound Maid Public with Tanya Katenjian, Philip Wood, Emma Vecchione, Sarah Conlisk, Alessandro Santoro, and Jeremiah Moore. Lead funding for the digital collections of the Carnegie Hall Susan W. Rose Archives has been generously provided by Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Susan and Elihu Rose Foundation and Mellon Foundation with additional support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Film Preservation Foundation, and the Metropolitan New York Library Council. Our show is distributed by WQXR. We'd like to thank our partners there, including Ed Yim and Elizabeth Nonemaker.

To listen to the full season, subscribe to if This Hall could Talk wherever you get your podcasts. If you like what you hear, please support the show by sharing it with your friends and leaving us a review and a rating on your favorite podcast platform. And if you happen to come across some special artifact from the history of Carnegie Hall, let us know.

You can reach us at if this hall could talk@carnegiehall.org. We're always on the lookout. Thanks for listening. I'm Jessica Vosk.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio and Carnegie Hall. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.