Otello: Black Handkerchiefs Matter

Terrance McKnight: This is Every Voice with Terrance McKnight. It’s a new podcast from WQXR that interrogates the culture of our classical music scene and we look at ways to make it beautiful for all of us. In this series we’re talking about representations of blackness in opera. Today we’re talking about Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello.

Dr. Uzee Brown: This is a character who faces a unique kind of human dilemma. Jealousy is something that plagues this man.

Kevin Maynor: My understanding of Othello is one that is gullible and can be fooled easily. His ego can be easily bruised.

Iago/Thomas Hampson: He gets duped by some bullshit with a, with a handkerchief. Are you kidding me? He looks good but he’s not good.

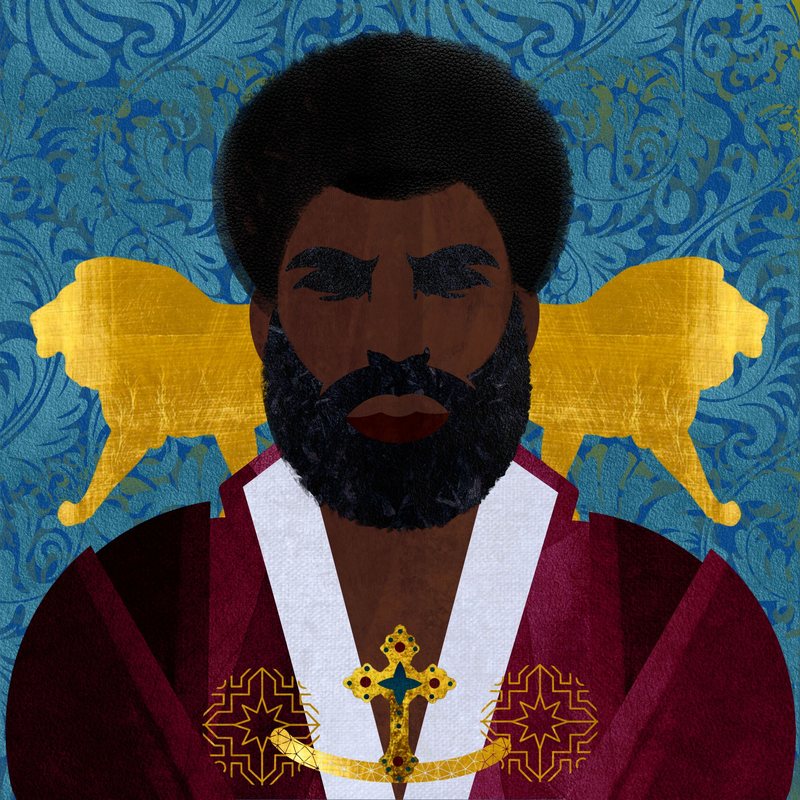

Limmie Pulliam: First and foremost he’s a Moor.

[CUE:MUSIC: “Tito’s Wisdom”]

Terrance McKnight: That’s right, first and foremost he’s a Moor. He represented those Africans who for 800 years, until around the year 1500 they ruled and developed agriculture, science, education and the arts in the area of the world now known as Spain. So when the Moors were expelled from Spain by Christians, they were forced to leave the area or convert to Christianity.

Peter Sellars: Shakespeare was writing for an audience at that moment. He was writing this topic because they were right in the teeth of colonialism. Colonialism was being invented in their generation. And so yes, they were seeing African people coming back on ships and stuff. So yes, they were dealing with it very directly. And it's a very alive topic.

TERRANCE: So Shakespeare wrote about a man who had been enslaved, who converted to Christianity, joined the Venetian army, ascended to the ranks of general, married a Venetian socialite, this guy was living what some would consider the American dream long before America existed.

But of course that story couldn’t end there with a free black man marrying a white woman and living free and happily ever after? That was counter to the politics and social agenda of the 17th and 19th centuries.

When Verdi’s Otello came to America in 1888, interracial marriage was unlawful in most places. And the idea of the free black man represented someone to fear.

Jasmine Ogiste: The New York Age, Thursday, February 17th. 1910, big, black, burly brute, four white men, not many weeks ago were confined at one time in the jails of Georgia for assaults upon white women.

In each case, the white men attempted the unmentionable crime while blacked up as a negro in each [00:15:00] community, a mob of infuriated proud Caucasians quickly gathered at the behest of flaming headlines of the local press to hunt down the big black burly. And to avenge the womanhood of their. But the thin veneer of burnt cork…

Seeking a black brute, Chattanooga, Tennessee, April 11 News comes from Iuka Mississippi.

That 500 people are armed and scouring the country in search of a negro named Johnson, who on Thursday night. Entered the house of James Thompson during his absence and brutally assaulted his wife. The lady is 60 years old and will probably die of the shock and injuries received at the hands of the brute Johnson will be hanged by the excited people if caught.

The New York Times published April 12th, 1885.

Terrance McKnight: In 1888, the year Otello came to the US, 69 black people - mainly men- were lynched in America. In Virginia alone, 26 Black men were lynched between 1880 and 1897. And in the 19th century, 38 states had miscegenation laws, statutes at one time or an other, preventing the mixture of what was considered inferior and superior races.

In Georgia, I think it was 1869, a court ruled that the offspring of intermarriage are generally sickly and effeminate and are inferior in physical development and strength to the full blood of either race. This was the climate that Otello was presented in, in America. So Verdi’s Otello really sounded the public fire alarm. It signaled the danger of the free black man. The thinking was “ Given complete freedom, these men pretend to love Jesus, take up arms, then they run off with our daughters. There goes the neighborhood. So we gotta monitor them and contain them.”

Peter Sellars: So Othello is a very strange animal. I can’t stand that play, I hated it for years, and I got into a huge huge argument with Tony Morrison. We spent 3 ½ hours one day just going around about it.

And she said, no, it’s not about him. It’s about Iago. This is the language they are still using to promote fascism in this country. This is the language they are still using, the suggestion, the not upfront, the coded racist language. In fact, all of the racism is only, you know, made possible by, uh, complicity of silence. And for people who know perfectly well what the truth is and are not gonna say it in public.

[CUE:MUSIC: “Tito’s Wisdom”]

Peter Sellars: You’re listening to Every Voice…

Terrance McKnight: You’re listening to Every Voice with Terrance McKnight. We’ll be back after this break.

[MIDROLL BREAK]

[CUE:MUSIC: “Sunrise”]

Terrance McKnight: Publications in the late 19th century depicted black men as brutes…

[CUE:MUSIC: “Act 3 Overture - Livermore Opera”]

Publications like Troubled Heritage, Beauty Beast, how Sleeps the Beast, Betty Page, comic Strips and movies did the same.

The most well known is Birth of a Nation, that film that was screened in the White House in 1915 with President Woodrow Wilson. Members of the cabinet, and the president’s family was in attendance. That film had white actors in blackface portraying black men as stupid, you know, unintelligent, sexually aggressive towards white women. And so with that caricature that was so highly publicized - of the black man as a brute - and his humanity is always in question.

Otello is a good example of the brute. He’s insecure, jealous and full of rage: and a threat to white womanhood. In the opera Otello gives his wife a handkerchief. It’s a memento and a symbol of his love for her. Iago, his colleague and nemesis, knew about the handkerchief and probably what it meant to Otello. So he convinced his wife who was Desdemona’s maid, to steal it from Desdemona. You know how Iago felt about Otello and Desdemona, listen to him talking about his own wife.

IAGO: She cooks, she takes care of things. She got the house in order. I don't, you know, she's, She has no idea who really I am, doesn't, you know, [00:08:00] she's irrelevant, obnoxious at worst, . She doesn't know who I am. She's got no idea. She'll find out. Yeah. Doesn't matter. She'll run, she'll go, doesn't matter. I don't, I'm not at this point, I just live inside myself man.

Terrance McKnight: What he wanted to do was bring Otello down, he stated he wanted him dead and he knew the handkerchief had special significance to him and Desdemona.

[CUE:MUSIC: “Livermore Opera”]

Terrance McKnight: So he had his wife steal it from Desdemona so that he could plant the handkerchief with another man to make it appear that Desdemona had been spending intimate time with someone else. Iago’s planned worked and that’s when Otello just lost it, became unreasonably upset, irrational, because that little handkerchief represented everything to him. And that handkerchief wasn’t white, it was black. So this handkerchief that Othello became so enraged about was a black handkerchief, and it was connected to his heritage. The heritage he had to publicly distance himself from just in order to live in Venetian society. But having people play games with that handkerchief was like playing games with his momma.

Terrance McKnight: So that further explains why he was so enraged about that handkerchief.

Maribeth Diggle: Yes. If you play it as a white handkerchief…

[CUE:MUSIC: “Livermore Opera” contd.]

Maribeth Diggle: And if you, I mean, if it's a black [00:40:00] handkerchief, then it really is a, a slap in the face of course. Um, because it is such a personal item for him. It's not just a handkerchief, it's not a, you know, like just a, a thing to wipe your brow. It is, it has familial historical value and also tells a lot about the, the personal past of his race.

But over the years, when you go to a performance of, of Othello today, the handkerchief is, is white. And I think it's so fascinating because it. It's literally whitewashing the, the most important piece of evidence. And it is literally whitewashing, Othello's body. I feel the, the handkerchief is, is related to Othello, and originally I think he knows the meaning of this black piece of fabric, and it would've been performed in Shakespeare's day as a Black handkerchief, which maybe comes back to your question about Shakespeare's political wishes to speak about race. I guess we'll never know, but I think it's important to say that he understood the significance of this handkerchief being black and over the years of European directors directing this piece, the handkerchief became Desdemona’s body by becoming white and and washed away the history with it, this piece of history.

[CUE:MUSIC: “Tito’s Wisdom”]

Terrance McKnight: In this podcast we bring the past into the present, the stage into the streets where we all walk, live, work and love together, trying to make things more beautiful for all of us. Thanks to Maribeth Diggle, Thomas Hampson, Limmie Pulliam, Peter Sellars, Dr. Uzee Brown, and Kevin Maynor for joining us in this episode.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.