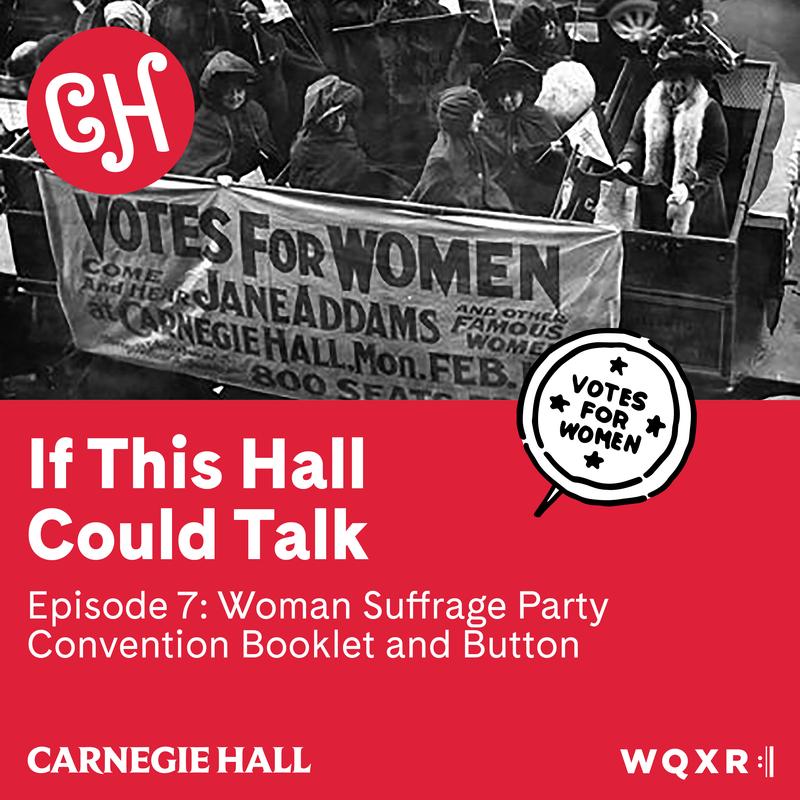

Woman Suffrage Party Convention Booklet and Button

IF THIS HALL COULD TALK: WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE PARTY CONVENTION BOOKLET AND BUTTON

Marcia Chatelian: I think it's so important that cultural institutions understand they need to be a gathering place for people to reflect on political ideas, and that the works they present have to be a reflection of the artistic manifestation of people grappling with politics. It's perfectly aligned.

Susan Ware: It's wanting to be where the power is, to be where the influence is, and to say, "We belong." And Carnegie Hall would be an obvious magnet for the suffragists.

RECORDING OF “SMILES FOX TROT” PERFORMED BY JAUDAS’ SOCIETY ORCHESTRA.

Jessica Vosk: Welcome to If This Hall Could Talk, a podcast from Carnegie Hall. I am your host, Jessica Vosk and in this series we’ll look at the legendary and sometimes quirky history of the Hall. From momentous occasions to the eclectic array of world-renowned artists that have taken to the Hall’s stages, in each episode, we’ll explore unique items from our archives collection and travel back in time to relive incredible moments that have shaped the culture we live in today.

For this episode, A Leaflet and a Button of the Suffragists Rally at Carnegie Hall.

RECORDING OF “COLUMBIA’S DAUGHTERS” PERFORMED BY ELIZABETH KNIGHT.

Jessica Vosk: For decades, the right to vote was given only to men. First just white men, then, after slavery was abolished, Black men too.

On August 18th, 1920, after a tremendous effort by women on both this side of the pond and the other, the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote. Today, we tend to take voting for granted, of course women voted, we take up half the population. But if history tells us anything, it’s that nothing should be taken for granted. A lesson we need to keep learning again and again - especially during these times when voting rights are once again under attack. So hearing the struggles that women across the nation went through all those years ago, reminds me of just how important it is to value and defend the right to use my voice. Marcia Chatelain is the 2021 winner of the Pulitzer Prize in History, a Professor at The University of Pennsylvania, and a speaker on race and gender.

Marcia Chatelian: What fascinated me about the story of the 19th amendment isn't just about how it got passed, but what it meant for women who were outside of the realm of voting for such a long time and the ways they made themselves legible and possible as citizens. And I think that one of the things that is so challenging about the period of time in which we live is that we talk about the importance of voting to young people, we talk about civic participation, but one of the things we have to keep in mind is that there are a lot of ways in which people assert themselves as members of society, as leaders, as activists that are outside of the right to vote.

Jessica Vosk: Susan Ware is a feminist historian and author of Why They Marched, a history of the women’s suffrage movement.

RECORDING OF “SMILES FOX TROT” PERFORMED BY JAUDAS’ SOCIETY ORCHESTRA.

Susan Ware: In our current political atmosphere, you don't have to make the case for why voting rights are important. It's just so apparent to us all that these battles are still being fought. And so, what I'm finding is that, instead of women's suffrage seeming like some distant, unimportant, small movement, it's one that first, you can get people excited about because it is a good story, but it's one that has all kinds of relevance to the political moment that we're in today.

Jessica Vosk: In this episode of If This Hall Could Talk, we’re going to learn about this extraordinary movement that got women the right to vote, and we’ll hear from offspring of the women that were at the center of it.

It’s also an episode to remember Andrew Carnegie’s dream for The Hall: he wanted to make sure the hall was

Gino Francesconi: “a platform for all causes. And, all causes may here find a platform".

Jessica Vosk: Rob Hudson is an archivist at Carnegie Hall.

RECORDING OF “CARRIE CHAPMAN CATT SPEAKING IN 1932.

Rob Hudson: I find the whole movement fascinating. Because, the roots of this go back to like 1840. It's tied up with the abolition movement, but then of course, it really takes on steam just after the civil war. But think about how many years they were fighting for this. I mean, if you go all the way back to 1840, it was 80 years. So just that determination and dedication to this, they just didn't give up and they could have. I mean, they were arrested, they were jailed, they were like forced fed in jail.

RECORDING OF “SUFFRAGETTES MEET AGAIN” 1955.

RECORDING OF “RAG-A-MINOR” PERFORMED BY YERKES JAZARIMBA ORCHESTRA AND JULIUS LENZBERG.

Jessica Vosk: The suffragist movement, and by the way what’s up with that name - it sounds so much like suffering! I think we need a rebrand. But I digress. The suffragist movement was no joke. These women were total bad asses and that set the stage for so much activism and progressive tactics that we employ today, like…

Coline Jenkins: They decided to picket the White House.

Jessica Vosk: This is Coline Jenkins. And she is not just anyone - she is the…

Coline Jenkins: “great, great granddaughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who, in 1848, demanded elective franchise for women. That's the vote for women.”

Jessica Vosk: She has dedicated her life to continuing the legacy of her great, great Grandma. So she knows this movement well.

Coline Jenkins: Well, back then, it was the first time the White House was picketed. And for two years, the Silent Sentinels stood by the White House gate in summer, in fall, in winter, in spring, with their banners saying, "Mr. President, how long must we wait for liberty?"

RECORDING OF “YESTERDAY’S NEWSREEL” FROM 1919.

Coline Jenkins: And the point was, America's fighting a war for liberty in Europe, but here, women of America did not have the fundamental right to vote. What type of liberty is that? And so, I admire them. And this is a little, tiny detail. How are you, in winter, standing for hours in front of the White House?

Do your feet get cold? Yes. Now, what did their sisters do? They took bricks, and put the bricks in their ovens, and then transported them to the front of the White House so that the women could stand on warm bricks, so their feet would not freeze.

RECORDING OF “GIVE THE BALLOT TO THE MOTHERS” PERFORMED BY ELIZABETH KNIGHT.

Rob Hudson: I mean, just the things that these women endured and the ridicule and everything else is just astounding. And so, like so many of these movements, I mean, you can compare it to the Civil Rights Movement of the '50s and '60s which took a lot of its cues in some ways, I think from the suffrage movement.

Marcia Chatelian: Black women in the suffrage movement were really helpful for setting a model of how you engage in politics, even outside of the right to vote because this becomes the basis for a lot of the community and institution-building that will give birth to the mid-century Civil Rights Movement, which again, pivoted largely on the right to vote and access to the ballot.

Rob Hudson: And so that early generation, it's almost like when you look at the earlier generation of civil rights leaders, like Booker T. Washington and some of the others that took a less confrontational approach. And then others that came along later and said, you know what, this isn't working, we really need to be in people's faces more about this.

RECORDING OF “A BIRD IN A GILDED CAGE” PERFORMED BY HARRY ANTHONY.

Susan Ware: When we sort of fast-forward to about 1900 or so, things are starting to pick up, and certainly by 1909, 1910, there's what I call kind of a quickening of suffrage activism, where all the sudden, instead of just being debated in church parlors and lecture halls, it's taken to the streets, it's in Washington, it's at Carnegie Hall.

Rob Hudson: You look at all these events at Carnegie Hall, and there was, depending upon how you count it, there was more than two dozen suffrage related events between 1908 and 1919.

Jessica Vosk: The very first event was on December 4th, 1908, when the Hall was, “filled to overflowing.” November 19, 1913 was the Thanksgiving Suffrage Rally. On May 2nd, 1914, was the Suffrage Celebration Day. October 30th, 1915 was an anti suffrage meeting and the final event was March 10, 1919. Two months later, the amendment passed the house.

RECORDING OF “YESTERDAY’S NEWSREEL” FROM 1919.

Susan Ware: The idea's to get the topic in people's face so they have to take a stand on it. And so, for me, the most exciting period of the suffrage movement really is its last decade, when it really blossoms into a broad social movement that encompasses the entire United States.

RECORDING OF “HANDS ACROSS THE SEA” PERFORMED BY THE NEW YORK MILITARY BAND.

Kathleen Sabogal: The strategy was to get the state by state amendments. And then some were like, no, we just have to go right for the federal amendment.

Jessica Vosk: Kathleen Sabogal is an archivist at Carnegie Hall.

Kathleen Sabogal: And something as a woman, thinking about this is like, wow, these women coming together and really wanting to vote and wondering how long is it going to take?

Rob Hudson: I mean, it was really quite an ordeal.

RECORDING OF “CARRIE CHAPMAN CATT SPEAKING IN 1932.

Coline Jenkins: They had radical ideas and radical actions, for instance, marching up 5th Avenue in New York City in a mass movement, a three-mile-long march.

RECORDING OF “WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE STOCK FOOTAGE” FROM 1914.

Coline Jenkins: And one of the things they did is, they rented Carnegie Hall, and they advertised it as being a suffrage event, my great, great grandmother spoke there, as well as they brought over a suffrage leader from England. And they advertised that it was free admission to all people who came. And what's interesting is, they filled the Hall, plus 1,000 people could not be admitted because there wasn't enough seats.

Gino Francesconi: It was standing room only.

Gino Francesconi founded the archives at Carnegie Hall.

Gino Francesconi: When I looked it up in The Times, the headline says, 5000 left standing outside at a manless rally, no men. And in fact, it said that every window and door that could be jarred open was tried and women actually got into the basement and were screaming trying to find their way up to the stage.

RECORDING OF “HANDS ACROSS THE SEA” PERFORMED BY THE NEW YORK MILITARY BAND.

Jessica Vosk: Just imagine it. What a sight that must have been. Thousands of women, marching for miles, right into one of the most respected and revered cultural centers in the US. And, as we touched upon earlier, this movement set the stage for so many others to follow.

Marcia Chatelian: One of the things you uncover when you look at the suffrage movement is that the activism that carries into the early 20th century, a lot of it has its origins in the abolition movement and slavery because it's tied around this idea that women have this special role to serve as the moral guides of society. There was no greater moral challenge in the United States than the institution of slavery. A number of the leading figures in suffrage, across the color line, they start philosophizing about the nature of rights and equality by looking at the issue of suffrage.

Coline Jenkins: It's called the world's greatest bloodless revolution. This is a revolution in America, and they never used the gun, they used their words. And that is the power of Elizabeth, of Harriot, of my grandmother. They had very powerful speech and very powerful arguments. I like to call them irrefutable arguments.

Marcia Chatelian: When I read some of the essays that these women wrote about suffrage, or I look at some of the images we still have left of them all dressed up, often in white dresses, going out to march, I just think about the fearlessness in every situation.

Susan Ware: One technology that was really important starting in the 1890s was a difference in how photographs could be reproduced in newspapers. In the 19th century, it had mainly been etchings. But by the 1890s and the early 20th century, photos could accompany a story, and of course, they're much more powerful. And so, the suffragists figure out – these are black and white photos, obviously–that if they wear white dresses, they will stand out even more in these photos. That is one of the reasons why in many of the suffrage parades, you'll see women dressed primarily for white. It's for contrast. And it's that kind of political savvy that I think really helps explain why, in the last decade, this movement really takes off.

Marcia Chatelian: The fearlessness required to take pen to paper and express who and what you are as a political person in an era when women were not believed to be political people, Black women particularly were not allowed that opportunity, and just the bravery that takes.

Jessica Vosk: You’re listening to If This Hall Could Talk. I’m Jessica Vosk. We’ll return to the show in just a moment. Stay with us.

[MIDROLL BREAK]

Jessica Vosk: Welcome back. Let’s get back to our conversation about the years leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment, which won women the right to vote … and the suffragists’ rally held at Carnegie Hall in 1910.

Coline Jenkins: How can you have a democracy where half the people are left out? And yet, you're making laws that they are compelled to obey. To me, that's all the reason you give a person a voice, which is a vote.

You and I are talking, we're making our voices heard, but how do we have our voices heard in a government? And that is through voting. And it's usually majority rule that creates laws that we're compelled to obey. Now, if you leave women out of having a vote, but also out of serving in government, serving on a jury, leaving them out of higher education, what's happened is that women are dead in the eyes of the law.

They don't really exist. They're outside the law. So to me, that's quite objectionable and worth fighting for.

RECORDING OF “WINNING THE VOTE” PERFORMED BY ELIZABETH KNIGHT.

Susan Ware: I think one of the things that we need to remember is that politics was a really male affair in the 19th century.

Jessica Vosk: Even more than today, that is.

Susan Ware: Political parties and voting were–it was like male bonding. You had your allegiance to either the Republicans, or the Democrats, or some third party. On election day, you'd get together, it would be like an all-day drunk. The voting took place in saloons, much alcohol was consumed, often violence broke out.

Coline Jenkins: Polling places were often in a hotel or in a saloon. And you have to realize, too, even in my mother's generation, a woman could not go up to the bar and order a drink. Only a man could order a drink.

RECORDING OF “WINNING THE VOTE” PERFORMED BY ELIZABETH KNIGHT.

Susan Ware: And here, you have women saying, "We want to vote." And there was a kind of disconnect, I think, between trying to imagine women inserting themselves into that dirty political situation, if you think about machine politics and the big city. And so, women really needed to make the case, and what they said was, "You need our perspective in politics. It's important."

Jessica Vosk: So now, let’s get back to Carnegie Hall. On October 28th, 1910, over 3000 women assembled in Carnegie Hall, spilling over into the hallways and the street. The event was a culmination of all the rallies and strategies that led up to it. Because women realized that taking to the streets and to the white house wasn’t going to cut the mustard, they needed to reach into culture, and what better place to do so than at the prestigious Carnegie Hall.

Susan Ware: As the movement matures, it becomes more and more savvy about how it's going to pitch its case and try and get women the vote.

Jessica Vosk: Carnegie archivist Kathleen Sabogal described the booklet and button.

RECORDING OF “BLUE ROSE WALTZ” PERFORMED BY JAUDAS' SOCIETY ORCHESTRA.

Kathleen Sabogal: It's a small booklet, I don't know, four by six or so. It's eight pages, which is, we call a souvenir program. It's got some staining on it, but it's nice because whoever this belonged to it was very important to them because they attached their ticket stub from where they sat. There's some handwritten notes of who, they listed the names and then it had the little votes for women button attached to it as well. And it lists all the different delegates from all over the five boroughs who were there.

Jessica Vosk: The excitement in the room was electric, women had marched into the Hall, and there were thousands more waiting outside.

Gino Francesconi: I mean, they had flags, they had carriages with banners. They had ribbons across their chest. They had the badges and the flyers.

Jessica Vosk: According to the New York Times coverage of the event, “the Woman Suffrage Party at Carnegie Hall felt as gloriously political as if the drama of woman suffrage were completed.” The leaders of the movement spoke that night: Ethel Snowden, Carrie Chapman Catt, Harriet Burton Laidlaw and, of course, Harriet Stanton Blatch.

Coline Jenkins: The other thing that's interesting about our 1910 booklet is that it lists all these women who were there for each of the different delegations from Manhattan, Queens, Staten Island, Brooklyn, their names and their addresses.

Jessica Vosk: New York was a hot bed but interestingly, the suffragists took a cue from the Western part of the US.

Coline Jenkins: …because the West was much more advanced in equality between genders. The roles were much more even. And so, what they decided to do, in the East, they started a campaign by saying, "Women of Wyoming can vote since 1869. Women of Idaho, California, all these women can vote in the West, but not in New York. Why not?" So, that was a good way to say, "Look, it can happen. It has happened. It works. Give us the vote."

Susan Ware: I think we sometimes look around us now and see social media and how quickly information is shared, and you think, "Oh, those poor suffragists. How could they possibly have mobilized a movement without all these tools?" And yet, I think a better way of thinking about the suffragists is that they were using the same cutting-edge tools that were available at the time that people are doing now when they're mobilizing. And they're really being innovative. And a lot of it, again, comes back to this theme of taking the movement out of the indoor settings and onto the streets.

Marcia Chatelian: I often feel is a great sense of just awe of the ways they made themselves so vulnerable in such a dangerous era and how they were able to maintain that commitment.

Coline Jenkins: Once the Empire State granted it, the other states fell like a deck of cards. And so, in 1917, women in New York state were granted the right to vote, and then 1920, all states had the legal right to vote, simply because it became part of the Constitution.

Jessica Vosk: Today, we know what a divided country feels like and the era of the suffragists wasn’t any different. There were many people, men and women, opposed to this movement. Why else would it have taken almost a 100 years?

Susan Ware: I think one thing we need to keep in mind when thinking, "Why did it take so long for women to get the vote?" almost 100 years, and that was because there was opposition to it. A lot of people didn't think this was such a good idea. And there are traditional opponents, like religious leaders, male politicians who were worried that women might vote them out of office, or industrialists who were worried that women might vote for labor laws. But some of the most potent and compelling anti-suffragists were women. And I think this is very confusing to people today. "How could women be opposed to having more rights?"

Marcia Chatelian: I think one of the issues we find with history is that at any given moment, a particular history can be used for a number of purposes, whether it's to revive a romance of what the past was like, whether it's to sort out complicated issues in the present, whether it's to search for heroes.

RECORDING OF “KEEP WOMAN IN HER SPHERE” PERFORMED BY ELIZABETH KNIGHT.

Susan Ware: In some ways, it was very threatening. If you think about a definition of gender roles where women are primarily seen as wives and mothers, and the male is the head of the household, and elevating the women to equal status really upends, in potentially some dramatic ways, how the family is organized, who is speaking for the family in public. It was something that a lot of people were concerned about, and we didn't really have a chance to talk about this, but in the midst of the suffrage movement over its long durée, there were major changes going on in women's lives.

Marcia Chatelian: I think the suffrage movement, for a very long time, was one of those topics that the characters in it were celebrated as these heroes of the past in kind of an uncomplicated and un-nuanced way, that these are the heroes of the past, and we should praise them.

Susan Ware: A lot was changing, and that was scary to a lot of people, men and women. And there also are women who are quite active in public events who say, "We don't want the vote because we think we will have more power and influence by keeping a nonpartisan stand." Because almost by definition, if you start voting, you have to declare your allegiance to one party or the other, and they want to have women participate in public life, but not necessarily do it through politics. And remember, politics was dirty business. And so, that stance isn't actually all that hard to understand.

Rob Hudson: Depending upon how you count it, there was more than two dozen suffrage related events between 1908 and 1919. Almost f you include some of the things like the anti suffrage. And so, this opposition, and so there was not that many of them, but there were events like that at Carnegie Hall, anti suffrage events.

RECORDING OF “FALL IN LINE” PERFORMED BY VICTOR MILITARY BAND.

Jessica Vosk: That’s just such a remarkable thing, the two voices of the movement, side by side. At Carnegie Hall.

Gino Francesconi: We had a rally and then right next to it, the very next night, I think it was the attorney general of the United States or the attorney general of the state of New York held a meeting called what men think about that meeting last night and they said those women were nuts.

Jessica Vosk: But according to Carnegie archivist Gino Francesconi, that’s what makes the role of Carnegie Hall so important. It was the venue of choice for both sides of the debate.

Gino Francesconi: And I just thought that's Carnegie Hall, here are the women and here are the men saying they're crazy. I just think that's great.

Susan Ware: That was the legacy of the suffrage movement. But having women stand up and say, "We don't want the vote," was a very powerful tool because then politicians could say, when a suffrage delegation came in, "Well, I just had a delegation half an hour ago from a group of women anti-suffragists, and they said they don't need the vote, they don't want the vote." And so, again, what you have is the two sides fighting it out in public, and in a site like Carnegie Hall, I'm sure there were many more pro-suffrage events, because New York really was a center of suffrage activism, but it was also a center of anti-suffrage activism.

Jessica Vosk: Ultimately, the role of a space like Carnegie Hall, of the arts, of culture, is to reflect what’s happening around it, to tell the story that shapes our reality, our nation, our world. So while we so often think of Carnegie as a performance space, we can also think of it as a place that both creates and reflects the culture we live in. In the two weeks surrounding this event, there were a number of other events happening: Classical performances by the New York Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, a series called Travel Talks, The Democratic State Campaign Rally, The People's Symphony Concert and even a lecture on London. Needless to say, the Suffragists were in good company. Again, feminist historian and author Susan Ware.

Susan Ware: When women are gathering at Carnegie Hall, they're not voters. And if they're there in 1910, they're not sure when they're actually going to get the vote. But there is a lot going on in that decade, and again, the phrase I use is the quickening of activism and really taking it to the public in a new way, including such venerable sites as Carnegie Hall, which conveys both respectability, and credibility, and also just a large public event where women are proud and willing to stand up and be counted in a public setting as suffragists. So, normously important.

Jessica Vosk: Marcia Chatelain thinks so too.

Marcia Chatelian: Culture is a reflection of the political yearnings, the political strivings, the political sensibilities of an era. And so, I can't think of a better place for a mass meeting on suffrage than Carnegie Hall.

It is where people gather to listen to, and to see, and to feel the culmination of ideas and of how people are interpreting what's happening at the moment.

Coline Jenkins: I like to remind America we started out with the Declaration of Independence, that all men and women are created equal. Collectively, two declarations. That we have these basic values. I want us to continue evolving our basic values and not forget who we or all the struggle it took to create who we are today.

RECORDING OF “SLIDING SID” PERFORMED BY THE NEW YORK MILITARY BAND.

Jessica Vosk: Many thanks to Clive Gillinson and the dedicated staff of Carnegie Hall, as well as guests Marcia Chatelain, Susan Ware, and Colleen Jenkins. You've been listening to If This Hall Could Talk, a podcast from Carnegie Hall, where we take you on a journey through some of the most iconic pieces in our archives, the objects that set the foundation for what the Hall is today.

For images of the artifacts and more information on Carnegie Hall's Rose Archives, please visit carnegiehall.org\history. If This Hall Could Talk is produced by Sound Made Public with Tanya Katenjian, Philip Wood, Emma Vecchione, Sarah Conlisk, Alessandro Santoro, and Jeremiah Moore. Lead funding for the digital collections of the Carnegie Hall Susan W.

Rose Archives has been generously provided by Carnegie Corporation of New York, Susan and Elihu Rose Foundation, and Mellon Foundation, with additional support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Film Preservation Foundation, and the Metropolitan New York Library Council. Our show is distributed by WQXR.

We'd like to thank our partners there, including Ed Yim and Elizabeth Nonemaker. To listen to the full season, subscribe to If This Hall Could Talk wherever you get your podcasts. We'd love for you to support the show by sharing it with your friends and leaving us a review and a rating on your favorite podcast platform.

And if you happen to come across some special artifact from the history of Carnegie Hall, let us know! You can reach us at ifthishallcouldtalk@carnegiehall.org. We're always on the lookout. Thanks for listening. I'm Jessica Vosk.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio and Carnegie Hall. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information. New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.