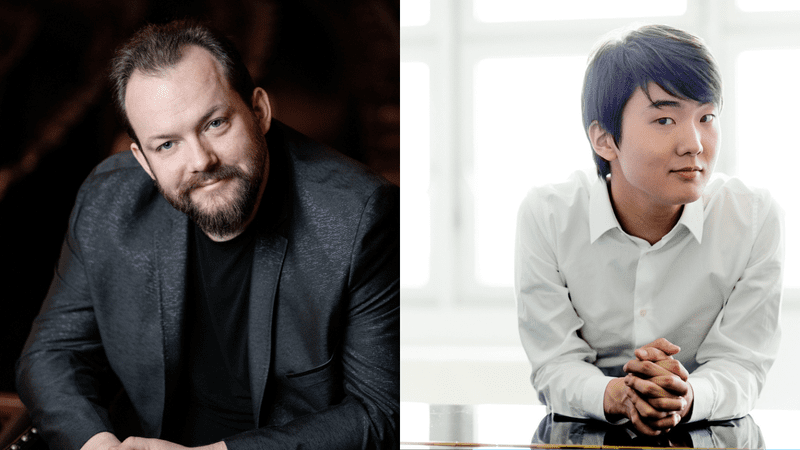

( Carnegie Hall: Marco Borggreve & Harald Hoffmann, DG )

Where to? Carnegie Hall, please. Okay, here are your tickets. Enjoy the show. Your tickets, please. Follow me.

Jeff Spurgeon: On this broadcast from Carnegie Hall Live, we're going to bring you a performance by one of America's most renowned symphony orchestras, the Boston Symphony. They have a wonderful home in Boston, but they've come down the East Coast to join us and a New York audience here at Carnegie Hall, bringing with them a program of music by Tania León, Maurice Ravel, and Igor Stravinsky.

Backstage at Carnegie Hall, I'm Jeff Spurgeon, alongside John Schaefer.

John Schaefer: And, uh, Jeff, this orchestra, it is one of the original Big Five here in the United States. Traditionally, the Chicago, Philadelphia, Cleveland Orchestras, the New York Phil. and the Boston Symphony. They've been around for almost a hundred fifty years and they have a distinguished musical history.

Some of the best conductors and music directors of the 20th century like Pierre Monteux, Serge Koussevitzky, Eric Leinsdorf, and Seiji Ozawa.

Jeff Spurgeon: And we are not quite ready for the arrival of their current music director, but he'll be here in just a moment, Andris Nelsons. Meanwhile, John and I are backstage. Unusually, the stage doors are open tonight, so you're hearing a little more of the sound of the orchestra, which is almost all on stage right now, uh, warming up, practicing a few things.

And, uh, so, uh, we're awaiting the arrival in a moment or two of Latvian native Andris Nelsons in his 10th season with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. And, uh, just in the last few days, it was announced that he has, well, we could call it a rolling evergreen contract, rather than a contract end date, uh, with the Boston Symphony. So they're basically saying to him, stay as long as you like.

Nelsons is also taking on a new educational role as head of conducting, at Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony.

John Schaefer: Up in the Berkshires, where, uh, for, for decades, the Boston Symphony Orchestra has spent summers playing and teaching and being a part of, uh, the community there in Western Massachusetts.

A little bit more about Andris Nelsons, before he was a conductor, he actually started as a trumpet player at the Latvian National Opera Orchestra, which he would then go on to conduct. He also led the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. He's also leader of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in Germany, but during his time with the BSO, he's done tours of Europe with the orchestra, he's toured Japan, they have a regular recording contract with Deutsche Grammophon, and Jeff, as you mentioned, they've got three works prepared for this concert tonight. The Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand, Stravinsky's evergreen Rite of Spring, but we're going to start with a piece by the Cuban born, long time New York based composer Tania León, and it is, in fact, her Pulitzer Prize winning piece called Stride.

Jeff Spurgeon: Tania León studied the piano from the age of four. And then got a bachelor's and master's degree in Cuba.

In 1967, though, she left that land. She was a refugee on one of the Freedom flights to Miami. A little reminder of that history after Castro took over Cuba, Cubans who had relatives in the United States were allowed to leave Cuba. So the U. S. set up what were called Freedom flights. They left Cuba twice a day, five days a week.

And those flights left Cuba twice a day, five days a week, for eight years. Amazing.

John Schaefer: And Tania León was on one of them. Landed in New York. Didn't speak any English, but that didn't stop her. She went and studied at NYU. And for decades now, she has been a real cultural leader here in New York. She was a founding member and the music director of the Dance Theater of Harlem.

She started the Brooklyn Philharmonic's Community Concert Series. She was music advisor to the American Composers Orchestra, often promoting music by composers with Latin American backgrounds, and for several years she was the new music advisor to the New York Philharmonic. And now she is the founder and artistic director of the organization known as Composers Now. And Jeff, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at CUNY. I'm out of breath just reading her resume.

Jeff Spurgeon: She's also a conductor and part of Uh, her education came from attending workshops, indeed, at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa. And Tania León has a very specific connection to Carnegie Hall this season. She is the occupant of the Richard and Barbara Debs Composers Chair for the 2023 24 season. She's a Kennedy Center honoree, and, uh, in 2021, as we mentioned, she received the Pulitzer Prize for this work. Stride.

John Schaefer: It was commissioned, actually, by the New York Philharmonic. It was part of their Project 19, which marked the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote. So the Philharmonic commissioned 19 women, including Tania León, for this project. And León started by researching the suffragette Susan B. Anthony, and this is what she said about that research into Susan B. Anthony's work. She said, " She kept pushing and pushing and moving forward, walking with firm steps, until she got the whole thing done. That is precisely what Stride means. Something that is moving forward." And I gotta tell you, Jeff, Um, this is a piece with a lot of forward momentum.

Jeff Spurgeon: She said that, uh, that that's what she meant by . It has some of what, to her, are American musical influences, or at least American musical connotations. A section where you can hear horns with a wah wah plunger, reminiscent of Louis Armstrong. Doesn't have to be indicative of any particular skin tone, it just has to do with the American spirit.

John Schaefer: It is American music in its widest angled sense. It's music that reflects the United States, but also Latin America in some of the rhythms.

I will say that the horn playing in this piece, the horn writing, is breathtakingly assured. It's one of the strong points of the work, and having been on that panel that awarded this piece the Pulitzer Prize, I can tell you that that is something to listen for. Here it is, Stride, from Carnegie Hall Live.

MUSIC: TANIA LEON’S STRIDE

John Schaefer: From Carnegie Hall Live, you've heard Andris Nelsons conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra in a piece by the Cuban American composer Tania León called Stride. That is the work for which she won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2021. A work full of forward momentum. Jeff, you could hear that some of the strides are halting.

(Yes.) This is a piece about women getting the right to vote through the 19th Amendment.

Jeff Spurgeon: It's not always steady progress, it comes in fits and starts.

John Schaefer: And Tania León, the composer, is here in the house and is now making her way on stage to take a bow. Greeting the conductor, Andris Nelsons, at center stage here at Carnegie Hall. A very popular figure among musical circles here in New York for quite a while. And the work that features some wonderful kind of echoes and evocations of her own Afro Caribbean roots in the rhythm, but really just a piece that is a virtuoso showpiece for the entire orchestra.

Jeff Spurgeon: Everyone is on his or her toes throughout this piece.

By the way, we should say too that this is the first time this work has been performed in Carnegie Hall. Right. This was given its, uh, its premiere a couple of years ago up the block a bit at Lincoln Center, uh, by the New York Philharmonic. But this performance by the Boston Symphony is the first time the work has been performed at Carnegie.

We are, uh, just through the first part of a three-part, uh, work for this concert by the Boston Symphony. Three works on this program. We've heard Tania León's Stride. And now there's a great deal of movement, uh, onstage and offstage where John and I are. And some of that movement will include a piano coming on stage for our next work, which is Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand.

John Schaefer: And it will feature the young Korean pianist Seong-Jin Cho, and Jeff, you'll remember the last time we had Seong-Jin Cho on our Carnegie Hall Live broadcasts because it was, um, a newsworthy event.

Jeff Spurgeon: For sure.

John Schaefer: It was, uh, February of 2022, the Vienna Philharmonic was scheduled to play with conductor Valery Gergiev and pianist Denis Matsuev.

But this was also at the time that Russia had just invaded Ukraine, so some artists, or some artistic changes were in order. Gergiev and Matsuev had both been public supporters of the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, and so the cavalry came over the hill.

Jeff Spurgeon: Yeah, and indeed they did. It was Yannick Nézet- Séguin, the conductor who was, who made himself available to be on the podium, and the soloist, they found, also appeared as if from nowhere, but he came from, back from a long way away.

Seong-Jin Cho was in Berlin. And he was reached about 36 hours before the concert occurred and asked if he'd like to play the Rach II with the Vienna Philharmonic. And...

John Schaefer: Rachmaninoff Second Piano Concerto at Carnegie Hall. Just, just toss that off if you would.

Jeff Spurgeon: Are you ready? And he said yes. He hadn't played the concerto for several years in nearly three years. But he spent the night at a hotel piano. Uh, in a, in a hotel lounge in Berlin, and caught the flight that he could get, and got to New York, and performed the concert, and it was really an amazing night. It was an incredible concert, perhaps you heard it in our broadcast here, so much excitement and incredible energy and goodwill for those last minute replacements a couple of years ago.

John Schaefer: Well, hopefully a little less excitement for, uh, our soloists tonight. Uh, not that the Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand is a walk in the park. The piece was famously written for the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who was the brother of the famed philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Paul lost his arm while fighting in World War I, but he wanted to continue performing, so when he returned, he commissioned a number of composers to write music for just the left hand of the pianist, and Ravel was one of the many who took up this challenge, and his concerto, really it is the centerpiece of the repertoire for the left hand.

And Seong-Jin Cho met up with our colleagues at WCRB in Boston for an interview about this piece, which he played with the Boston Symphony just a few days ago. This is what he said about the Ravel.

Seong-Jin Cho: I've been always loving this concerto since many years, and I always wanted to include this concerto in my repertoire, and I'm really glad that I'm finally be able to play this piece. And this piece is very different from the G major concerto, and I feel like this piece is more jazzy and has lots of character in the middle section.

It sounds like a, like military march a little bit, because Ravel composed this piece for Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his right arm during the war, and I feel like in this piece you can hear some tragedy, and also like a military march, but, you know, there's some kind of spirit in the piece, and I'm always imagining about war, and tragedy, and like, sometimes also very depressing.

Jeff Spurgeon: Seong- Jin Cho, talking about the piano concerto for the left hand that we're about to hear in this performance from Carnegie Hall. So that's some of the imagery behind the work, but we also talked to Seong-Jin Cho about the actual difficulty of just playing the piece.

Seong-Jin Cho: Even though technically it's so demanding, and I've never played a piece only for the left hand before. I think the music itself is so beautiful and wonderful, so when I play this piece I stop thinking about that I'm playing only my left hand. But of course it's so, it's so difficult, especially the cadenzas, they're so difficult and it's so tempting because I want to use my right hand also.

John Schaefer: All right, well, they'll have to tie Seong-Jin Cho's right hand behind his back, I guess, to avoid the temptation of using both hands.

Uh, I have to say, Jeff, that, uh, as with several of the pieces that Wittgenstein composed, uh, you would never know, unless you were a pianist yourself, that you were listening to a pianist playing with just one hand.

Jeff Spurgeon: Oh, it's extraordinary what, uh, what such artists are able to do. They really are quite amazing.

John Schaefer: And I wish I could say there's a happy ending to the story of Ravel and Wittgenstein, but Wittgenstein, when he premiered the piece, made some changes to the score that Ravel did not appreciate, and the two had a falling out and never reconciled.

Jeff Spurgeon: So, an interesting story about a great contribution to the piano literature, but which destroyed a friendship in the process.

By the way, we should also say thanks to our colleagues at WCRB in Boston and producer Brian McCreath for that interview with Seong-Jin Cho that we were able to share with you tonight.

And now with the stage set and the musicians all on place on the stage, we have just a moment of hesitation until those stage doors open and our soloist and conductor enter Carnegie Hall.

And there's the door and there goes Seong-Jin Cho and behind him, Andris Nelsons music director of the Boston Symphony. For a performance of this piece created by war, we could say. Born out of a wartime injury. And now one of the great parts of the piano repertoire. The Boston Symphony, Andris Nelsons and Seong-Jin Cho with Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand from Carnegie Hall Live.

MUSIC – RAVEL’S PIANO CONCERTO FOR THE LEFT HAND

Jeff Spurgeon: From Carnegie Hall Live, you've just heard a performance of the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand by Maurice Ravel. Composition played for you in this performance by Seong-Jin Cho, and the Boston Symphony conducted by Andris Nelsons.

A work that first saw the light in the year 1932, commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, Viennese pianist who was shot in the arm, he was a soldier in World War I. And captured as a prisoner, his arm was amputated to save his life. And he commissioned, as we've told you, as John mentioned earlier, a number of works for the left hand only, but this by far the most famous and most successful one and it really has entered the mainstream piano repertoire.

John Schaefer: Absolutely, and some of the composers that Wittgenstein commissioned included Benjamin Britten and Eric Korngold and Richard Strauss, so major composers wrote for this particular pianist with his particular limitation. But the Ravel piece really transcends any sense of limitation.

Jeff Spurgeon: And it's a wonderful companion to his other piano concerto. There are similarities and differences between this and the piano concerto in G.

John Schaefer: Yeah, it's a very yin and yang kind of thing, isn't it? The G major concerto, a very ebullient, brilliant work. And this piece cut from much darker cloth.

Jeff Spurgeon: Yes, a darker cousin, as I believe you said earlier. Yes, for sure. The Boston Symphony on its feet now. Andris Nelsons Nelson's pointing out various sections and individual members of the orchestra, and now the soloist and conductor are offstage for a moment, but, uh, well, there's always the anticipation after a major solo performance in a concerto that we'll have something more from the soloist, and that's, that applause is for Seong-Jin Cho. Back on stage now.

John Schaefer: He hasn't used his right hand yet. He should have plenty of energy left on that side of his body at least. But he has walked up to the piano, taken a bow, and is walking back off stage. We'll see what develops, but, uh, the piano concerto for the left hand, by the way, first performed here at Carnegie Hall by this orchestra in 1934. Serge Koussevitzky conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra with the pianist Paul Wittgenstein, but it's our pianist Seong-Jin Cho, who has taken his place back at the piano.

MUSIC – LISZT’S CONSOLATION NO. 3

John Schaefer: An encore performance by pianist Seong-Jin Cho, center stage here at Carnegie Hall, and the Consolation No. 3 by Franz Liszt, a solo piece of great delicacy and elegance from a composer we often associate with brilliant, virtuosic, explosive barn burners, but Liszt could do that as well.

Jeff Spurgeon: It's a beautiful poetic number, and, uh, we should add, too, that Seong-Jin Cho used both hands in that performance, just as the music is written.

John Schaefer: And, playing from memory, as he did in the Ravel, which was no mean feat, either. So Seong-Jin Cho, having played the Maurice Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand, now performs some music by Franz Liszt, to bring us towards intermission at what is a very colorful program that the Boston Symphony Orchestra and their conductor Andris Nelsons have brought to Carnegie Hall.

Seong-Jin Cho back out at center stage, enthusiastic applause from the audience here in the big hall, the Isaac Stern Auditorium at Carnegie Hall.

And that, uh, that will bring us to intermission here at Carnegie Hall, having heard the Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand written for Paul Wittgenstein, a piece, Jeff, that, as you put it, uh, was a product or by product of war.

Jeff Spurgeon: There's no question about it, yeah. Wittgenstein had a career and it, and it, uh, was transformed forever, uh, as the entire world was transformed, the entire Western world transformed by World War I.

And that can lead us, in a way to, uh, part of the focus of Carnegie Hall at this particular time in 2024, a new festival at Carnegie called Fall of the Weimar Republic: Dancing on the Precipice, a look at democracy and art, particularly in Germany in the 1920s and early 30s after the First World War, the start of the Depression and, uh, and the end of the democratic government in Germany, but also a look at the art world in that time, which was burgeoning and furious, we spoke with Carnegie's Executive and Artistic Director, Clive Gillinson, about why now seems to be the right time to look back on this particular era in Europe.

Clive Gillinson: I just feel democracy is something, I mean, you know, when one looks at the world as a whole, democracy is fragile and there have been periods throughout history where it seems secure and then somebody like Hitler comes along and you suddenly realize unless you nurture it and look after it, it can just disappear overnight.

And after all, Hitler was elected. Um, he was elected by democratic means and then used all the pillars of democracy to overthrow democracy. So, it, it was an idea I'd been playing with for a long time. And then, um, and of course it's controversial, but then that's what the arts should be anyway. You know, but the point is, we're never telling anybody what to think.

Uh, as far as we're concerned, what we're trying to do is raise questions, raise issues, look at some of the important issues of the day, and, and just make sure that people are thinking about them and talking about them. And I think it's stimulating curiosity and stimulating conversation that is a central part of our role.

Jeff Spurgeon: A look at the arts in the larger world from Clive Gillinson, Executive and Artistic Director of Carnegie Hall. Uh, Carnegie has festivals a few times during the year. They're generally a couple of weeks long, sometimes three. This particular festival is going to take up programming over a four month period at Carnegie Hall, and not just here. But at other institutions around the city, art museums, other performing, uh, organizations are all participating in this, uh, particular festival.

John Schaefer: And it's not just classical music, but, you know, you think of Weimar Republic, you think of cabaret.

Jeff Spurgeon: Oh, you bet.

John Schaefer: Uh, the influence of American jazz, you know. So there are lots of different musical threads being woven together in this ongoing festival about the arts and culture in Europe, and especially in Germany, but Europe as a whole in that period between the wars, and that again is, uh, this festival called Fall of the Weimar Republic: Dancing on the Precipice, and of course that precipice being the year 1933, as Clive says, the year that Hitler was elected Chancellor, and everything began to change.

Jeff Spurgeon: It's intermission at this concert that we're bringing you from Carnegie Hall Live, a concert by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

And before us now at our Carnegie Hall Live microphones are a couple of members of the Boston Symphony. So we are going to say welcome to violinist Jennie Shames and to double bassist Andres Vela. Welcome to both of you. Jennie, you've been in this, you've been in this orchestra for a little while. When did you join the BSO?

Jennie Shames: I joined the BSO in 1980.

John Schaefer: Wow. So?

Jennie Shames: Yes, I was five years old.

Jeff Spurgeon: That's a great line, and it works every time, doesn't it? Well done, well done. And Andres, you appear to be 10 or perhaps 11 years old at this point.

Andres Vela: Close, very much, yeah, very close.

Jeff Spurgeon: How long have you been in the?

Andres Vela: So, uh, I joined, um, in the fall of 2022 as a fellow.

Jeff Spurgeon: So you came in during the pandemic?

Andres Vela: Uh, yeah, towards the end, more or less, but yes, that's correct.

Jeff Spurgeon: Right, so, uh, normal orchestral life is something that you, in a way, are just beginning to experience with this ensemble.

Andres Vela: Yeah, absolutely, yeah. It's great.

John Schaefer: Now, Jennie, uh, in almost 45 years of playing with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, you will have played the Rite of Spring once or twice. How different is it every time with a new conductor?

Jennie Shames: It's very different every time. Surprisingly, because you think you know exactly the piece, and even with the same conductor, it's different every time. Funny story, the first time I ever played it, I had been in the orchestra for two months, and the Boston Symphony was going on its 100th anniversary tour, didn't have time to rehearse it because they knew the piece so well, and I ended up sight reading it on the stage of Carnegie Hall, and one of my, our, our timpani player back then, his name was Vic Firth, and one of my colleagues walked up to me as we were walking on this stage and she said to me, "Don't worry about anything. Just remember, when Vic plays, you don't."

Jeff Spurgeon: And that's, and that's how it works to be an orchestral musician. It's insights like these that we love conversations like this with you. I do have a question though. Jennie, as a long, a person who's played in the orchestra for a long time. You have a great home up in Boston. Symphony Hall is beautiful. What's different about Carnegie Hall, playing in Carnegie Hall?

Jennie Shames: Carnegie Hall, it's grander in a way. It's, um, they're both such iconic. halls with great iconic sounds. I have to say, we were talking about this last week, actually, especially bringing the Shostakovich here tomorrow night.

You can hear yourself much more clearly every note you play individually on Carnegie Hall's stage. It's, um, Boston Symphony melds the sound together so beautifully. Carnegie Hall does as well but on the stage itself you hear yourself much more clearly.

John Schaefer: Is that, can that be disconcerting? It's very disconcerting.

Jennie Shames: It's very disconcerting. It can be frightening sometimes.

John Schaefer: Andres, you joined the orchestra through the Sphinx Organization, right?

Andres Vela: Yeah, more, yeah something like that. Right.

John Schaefer: Explain what Sphinx is and what it does.

Andres Vela: Uh, so, uh, Sphinx, um, is an organization, um, uh, for, uh, Latinx, uh, uh, African American people. And, uh, every year they, they hold a, a conference, uh, where they, they hold competitions. Uh, they bring in, uh, people from, uh, professional orchestras to do, uh, master classes and, um, all, all sorts of stuff. And they do events throughout the year as well. Uh, so I've, I've been, I've sort of, through the last two, three years. Through their competitions and participating in some of their events, I sort of, you know, did that and then somehow just I just ended up here, you know.

John Schaefer: Yeah, somehow, yeah. Just found yourself in the Boston Symphony Orchestra at some point.

Jeff Spurgeon: But you also had some experience at Tanglewood, so you were one of the fellows at Tanglewood. What is that summer program?

Andres Vela: That's right. Oh, so, uh, yeah, I, so my first experience with Tanglewood was actually in the summer of 2020. It was like, we did like a virtual thing, so it was like middle of the pandemic, so I, uh, got to work with some of the.\ you know, faculty, which was, which was great. It was like a month long thing, but my first summer officially, you know, going was, uh, the summer of 2022. And, uh, yeah, just a lot of great stuff happening in this, uh, during the summer. Just a lot of chamber music, a lot of big orchestral works, a lot of pieces that I, uh, uh, for the first time was, Uh, playing, um,

Jeff Spurgeon: So you've done some sight reading in concert, too, then, just like Jennie did?

Andres Vela: Uh, something like that, yeah, yeah. It's, you know, I wish I had a fancy story about Rite of Spring, but this is actually my first time playing Rite of Spring. [Wow.] So it's, it's kind of interesting.

Jeff Spurgeon: So, Jennie, how do you help younger players move into the orchestra, learn the culture of an orchestra? I mean, most of it's sitting in the room and doing it, I know, but

Jennie Shames: I hope, in a lot of ways, I hope partly just by, um, example, by how I play on the stage, um, I hope sometimes by sharing. Um, what it used to be like, not in the sense of, oh, when, you know, in the old days when you didn't. I know, and I try not to, yeah. [I actually very much enjoy it, yes I do.] I used to love it, but through sort of memory of traditions, and actually sometimes saying how they've changed and how incredible they are now. I think through example and through a really welcome arms, um, because I love, I love the energy of the new players. I was one of the really young new players. And boy, I would look around and couldn't believe where I was. You know, as I still do, by the way.

John Schaefer: And what do you do in the summer? Does the whole orchestra go to Tanglewood?

Jennie Shames: Yes, yes, we all move out there. Tanglewood is actually, I find, our hardest season.

Jeff Spurgeon: Why is that?

Jennie Shames: Because we play three different concerts a week, um, on two rehearsals each, and they're hard programs, um, rather than one concert for an entire week.

John Schaefer: Right. And for folks who've never been, you know, the Shed is a unique experience for an audience. I'm guessing it's probably a little bit of a unique experience for you as players, too.

Jennie Shames: Yeah. It is.

Andres Vela: I think so. I mean, like, uh, well, like, I think, um, like, visually, it's, I think it's, for me, it's, like, very cool to see, you know, whenever you have everybody sitting in the Shed, and then you have, uh, all the people sitting on the lawn.

I think, like, I don't think there's anything that's quite like that, uh, you know, just the amount of people that just show up to some of these concerts. Um, but I also kind of like the, sort of like, the weather aspect, you know, like, we feel what they feel. [Right, right.] It's, yeah, it's, it's kind of interesting and cool, yeah.

Jennie Shames: It is true. It is. The Shed has remarkably good acoustics. It does. For an open sided. That too. It's, it's, it's not difficult to play in the, I mean. To us, it's, it's, it's our second home and it feels as comfortable, but it is a completely different experience.

John Schaefer: All right. Well, now you've got Rite of Spring at Carnegie Hall.

Andres, your first one. Yes. Jennie, you're [I don't even know]. Some number greater than one. Yeah. Jennie Shames, violinist. Andres Vela, double bassist. Two members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra joining us at intermission here. Thank you both.

Jennie Shames: Thank you so much. very much.

Jeff Spurgeon: Pleasure to talk to you indeed. We're at intermission of this concert broadcast from Carnegie Hall Live.

Classical New York is 105. 9 FM in HD; WQXR in Newark; and 90. 3 FM, WQXR, Ossining.

Backstage at Carnegie, well, you can hear the piano has been moved off stage. It went past John and me just a couple of minutes ago, very quietly moved by the stagehands, now tucked away here backstage. A few chairs reset, musicians moving around as you can hear some of them on stage, and, uh, and yet we're, we've still got a ways to go.

John Schaefer: We're moving on. Yeah.

A little more about our soloist tonight, Seong-Jin Cho, who performed that Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand, and then the Franz Liszt encore. His career took off after he won the prestigious Chopin competition in 2015. That competition only takes place every five years, and previous winners have included Marta Argerich and Maurizio Pollini and so on and so forth.

Uh, Cho has several recordings of Chopin's work, but he doesn't want to be labeled as the Chopin guy.

Seong-Jin Cho: Um, of course as a winner Of the Chopin competition, I had to play a lot of Chopin right after the competition, but I really didn't want to be labeled as a Chopin specialist because I wanted to play different repertoire as well, like Brahms, Mozart, Beethoven.

There's as a pianist, we are so fortunate to have so much repertoire. But now I feel like I don't care anymore, and I don't care what people say or I'll be honored if someone call me, he's a Chopin specialist. Yes, I'm playing Chopin's music, concerto, quite often and I'm planning to play more Chopin's solo music in the future.

Jeff Spurgeon: The voice of Seong-Jinchou, who played Ravel for us in this concert just a few minutes ago, and, uh, well, I guess it's now been three or four years ago, when he was at the studios of WQXR and shared with us some of that very well practiced Chopin he referred to. This is the fourth movement of Chopin's Sonata No.3 in B minor.

MUSIC – CHOPIN SONATA NO. 3 IN B MINOR

Jeff Spurgeon: The closing movement of Chopin's Sonata No. 3, played by pianist Seong-Jin Cho, a performance that took place three or four years ago at the studios of WQXR in New York. Right now, the WQXR microphones are at Carnegie Hall. We are at intermission of this concert by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Getting ready for the third and final work on this program, the legendary Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky.

I don't, I don't know, John, this piece is a riot, or at least it caused one, once.

John Schaefer: One of the most famous or infamous premieres in the history of art. Um, the, the premiere of this piece in Paris in 1913 was almost a literal riot. [I know.] Um. And there are sort of numerous conflicting reports about what caused it. Whether it was the music or the choreography.

Jeff Spurgeon: Costumes.

John Schaefer: Both of which were, you know, really pushing the envelope. Um, but just in terms of orchestration. Uh, first of all, the great and the good were in the hall that night. Among them, Camille Saint- Saëns, who according to the story, was already losing his sight. And the opening notes of Rite of Spring, he had to turn to his companion and say, What is that instrument? Only to be told it was a bassoon.

Jeff Spurgeon: Because it lies so high in the instrument. So high. So a real challenge, technically, for the players of that time.

John Schaefer: Right. And a bridge too far for Saint- Saëns, who was appalled at this, you know, at this misuse, in his hearing, of a wonderful orchestral instrument.

And Rite of Spring is full of all kinds of unusual rhythms, uh, kind of stomping meters, and

Jeff Spurgeon: And it doesn't, and it doesn't sound so odd to us now, because we've been hearing it for a hundred years, and yet it still has, the word is savage. It has a savage power.

John Schaefer: Yeah, well, I mean, it tells a savage story. I mean, it is a tale of a kind of prehistoric dance ritual and sacrifice, and, uh, just a remarkable piece of music that has still the power to surprise and shock.

Um, most people remember their first Right of Spring. I certainly remember mine. It was here at Carnegie Hall in 1980, San Francisco Symphony. I might be off by one year, might have been 79, might have been 81, but I think it was 80. First half was a work by the recently deceased David Del Tredici and Isaac Stern, before this auditorium was named after him, played the Sibelius Violin Concerto.

After intermission was the Right of Spring and in 1980, Jeff I, I kid you not, half of the audience did not come back after intermission.

Jeff Spurgeon: How about that?

John Schaefer: Afraid still of this piece. Something about this piece. It is now one of the signal works of the 20th century and a genuine classic. And we will now hear it performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andris Nelsons, who is back out at center stage here at Carnegie Hall. To perform Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring.

MUSIC – STRAVINSKY’S RITE OF SPRING

John Schaefer: From Carnegie Hall Live, Andris Nelsons leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra in a performance of The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky. Massive orchestra on stage in the main hall, the Isaac Stern Hall here at Carnegie Hall, and they're all on their feet. Applause coming from the crowd here at Carnegie Hall for that performance of what is one of the classic pieces of the 20th century, and a work that composers after Stravinsky had to deal with one way or another. The primacy of rhythm in that work. Partly because of its roots in the dance, uh, is something that changed music in the hundred plus years since it was first debuted.

Jeff Spurgeon: Other composers had to reckon with it, and in a way, Stravinsky didn't have to reckon with it, because he said, he wrote that, I was guided by no system whatever, in La Sacre du printemps, the Rite of Spring.

Stravinsky wrote, "I had only my ear to help me, I heard and I wrote what I heard. I am the vessel through which the Rite passed." So, yeah, he never wrote another piece that was quite like this.

John Schaefer: No, he never did.

Jeff Spurgeon: And so this was a, it was a one off and a remarkable thing. And as much, should we say, noise is generated by the orchestra in this piece, it's programmed very completely.

The outline of the ballet is easy to see. The various dances, the plans, the argument. And then, of course, at the end, this sacrifice of a, of a young girl, and it sounds primitive and impossible to believe. On the other hand, go grab a copy of Shirley Jackson's The Lottery and see how far away from this we really are.

John Schaefer: Yeah, uh, Andris Nelsons is back at center stage now and pointing to various members, various sections of the orchestra. And the other thing, Jeff, is that while it is a huge orchestra and they are deployed en masse during these big dances, the orchestration is also a thing of beauty unto itself, because Stravinsky really does have these moments where he lets all these different subtle textures come through, and it is as much a part of the impact of this piece as those you know, those, those strong but, but unexpected rhythmic accents and the, the quotes of folk song that litter the piece.

Jeff Spurgeon: And as you say, uh, as we started at the beginning, the, the beginning of it is a surprise. It lies very high in the, in the tessitura of the bassoon. And so there are, there are sounds that are surprising because they are in the orchestra, but deployed in unusual ways. And that's another reason why this piece has such incredible sonic impact. It's stuff you don't hear a lot in other places.

John Schaefer: And for a work that is now well over a hundred years old, that's, that's saying something.

Jeff Spurgeon: Yes, it sure is.

John Schaefer: Because a work like this usually spawns a host of imitators, and this, the Rite of Spring certainly did, but none have quite reached that mix of subtlety and power that, uh, that Stravinsky found somehow.

Right now the, uh, the brass members of the Boston Symphony are standing at Andris Nelsons Nelson's invitation. And he just held his two fists and shook them back a little bit in front of each other. So that means the timpanist should stand for a, for a note of applause.

Of course, they've been standing all the time, but yes, huge roar for the percussion section, which in this case you could argue is the entire orchestra.

And now, a bow for the various, uh, leaders of the string sections of the Boston Symphony, and now the entire orchestra, on their feet, acknowledging the sustained ovation from a packed house here at Carnegie Hall.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra, one of the original Big Five here in the States. There was, uh, New York, Cleveland, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston.

We don't really talk about the Big Five anymore because you could easily add another five to that list these days, but in the old days they were known as the, uh, the Big Five, the five sort of platinum orchestras of the United States.

Jeff Spurgeon: And the BSO has had steady recording contracts through their history and continue another series now with music director Andris Nelsons, who has, uh, an extension to his contract that is basically just rolling over into the future.

John Schaefer: As long as he wants to stay, he can stay.

Jeff Spurgeon: They'll have him here in, in, in Boston as the head of the Boston musical organization. And he's also taken a new job now, uh, as, uh, head of the conducting program at Tanglewood at the Summer Music Festival, which we talked about at intermission with a couple of the players.

John Schaefer: And finally Andris Nelsons is attempting to leave the stage. We'll see if the audience lets him stay offstage after that performance of The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky.

And the members of the Boston Symphony now beginning to file offstage as well. And joining us now at the microphone is the conductor, the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra himself, Andris Nelsons. Taking a seat to join us, well-earned after that performance.

Andris Nelsons: Yeah, hello, hello everyone, I hope you heard that.

Jeff Spurgeon: Yeah, that's a piece you can hear. That one comes through.

John Schaefer: That one's hard not to hear.

Jeff Spurgeon: Well, congratulations on a performance. It's um, it's, is it ever automatic? You've done this piece a number of times, and yet there are surprises all the way through it. What keeps you on your toes in this piece?

Andris Nelsons: You know, it's, it's like with actually any piece. When you, when you come back, even the piece you have done many times. You always take a score and you open it and you always analyze it again and again and you find new things. Sometimes, accidentally, you just think, oh, oh, how did I not notice that? And sometimes musicians give you the…you rehearse and you hear, oh, there is a clarinet or somebody offering you something which is very interesting and so, so it's I think it's a constant development and either it's Rite of Spring or any Beethoven symphony or, or any piece really but, but of course Rite of Spring it's, they sometimes call that the, the score of Rite of Spring is like a, like a bible for the instrumentation for composers because it's, the work Stravinsky has done, it's not only emotional and intellectual, because it's a revolution what he's done with this piece, but it's also, uh, you know, very master, mastery of, you know, of…

Jeff Spurgeon: The full understanding of all the instruments and what they can do.

Andris Nelsons: they can do, yeah. So that's, very often everyone says, Oh, okay, if Stravinsky writes that, so we can, That all, that instrument can play so high or so low.

Jeff Spurgeon: Well, he's stretched the technique, for sure. He's, he's, uh, he pushed those musicians to do better than they had done. And what we hear all the time is that, is that younger orchestra players have incredible technique. They are able to deal with these pieces.

Andris Nelsons: Yeah, I must say it's very interesting. You know, when it was premiered and performed in the Champs-Élysées from Paris, that was, at first, it was a silence, but then it started to become, people started to shout, they couldn't hear, and they couldn't figure out, what is that instrument starting this song? Because bassoons at those times, even they were good, certain technique, but Stravinsky knew it's almost impossible to play, or maybe at that time it was actually impossible to play in a beautiful sense. So it's almost something between bassoon, saxophone, and clarinet, you know.

John Schaefer: Well, and, and that, but that fit the, the dance, which was not intended to be beautiful.

Andris Nelsons: Yeah, exactly.

John Schaefer: It was intended to be raw and primitive.

Andris Nelsons: It's raw and primitive, and so that's, in a way, we, with the years, have, I think the, the interpretations of Rite of Spring has changed, and from one side, maybe because the technical level has grown. Musical level, of course, I think, I think it is still, still there. It's been always there. I think, not saying that you have to have a lot of mistakes, not at all. But I think that there is some raw, I can't say ugly, but raw and basic

John Schaefer: Something elemental, yeah.

Andris Nelsons: And you have to, it can't be to be [ sings out a rhythm]

Jeff Spurgeon: You have to, it has to be attacked.

Andris Nelsons: It has to really, you know, and if, if you manage to combine this roughness, plus the technical, technical quality of it, that goes, the piece is shining more and more. And of course, I'm so privileged with the Boston Symphony, it's, it's the highest technical playing, but also I love what the orchestra is that they always take care, I think, of both sides of music making.

One is, of course, is technical ability to play everything very, very professionally. But I think there is also always an urge to, to dig deeper and think what is about, what happened there? So, you know, either sacrifice or Or dance, you know, he's dancing to his, her death, and this is really crazy. And of course, if you know that, and try to play with different, uh, feeling, it sounds also different. I mean, I'm the one of those people who thinks that this is a very raw piece of meat.

Jeff Spurgeon: Has been now for more than a hundred years. Well, your leadership in Boston has been saluted by a new contract, and you have new work to do at Tanglewood, uh, as the head of conducting. So, what is your drive forward now, as you look at this, at this new part of your career in Boston?

Andris Nelsons: Yeah, well, um, firstly, the first ten years have passed really Really quickly, of course, in the middle of it, we had Corona and, and disasters, some events, but, but generally, the 10 years have passed quite quickly, and I, and I, I don't want to leave, you know?

Jeff Spurgeon: You don't have to.

John Schaefer: They clearly don't want you to leave.

Jeff Spurgeon: Yeah, you can, you can stay.

Andris Nelsons: Very happy today. We have an evergreen contract, so which we, we continue as far as, as we enjoy each other and enjoy making music together because that's the, uh, and, uh, we have plans of, yeah, different, also some repertoire we have already played, but some repertoire we want to play, maybe there is some repertoire which we didn't play, and also we want to continue recording projects with Deutsche Grammophon, and, and, uh, next season is an amazing, uh, Shostakovich Festival, which is a joint commission, not commission, excuse me, which is a joint, joint project with Gewandhaus Orchestra and we all, so also that thing is still continuing. And then, yeah, and me teacher, that's also strange, but very new, but I, I love, I love sharing. I wouldn't call it teaching because I don't think you can teach to conduct. You can, you can give advices, you can try to suggest and try to someone, even technically to try some, some exercises or some training, but it doesn't guarantee that you can really train. That the conductor you are working with will be a conductor. It's a very kind of profession which needs more time to, and also the time to learn who are you, you know, and because you are exposing yourself to the orchestra or to the ensemble or to, to, so it's really, I'm, I'm excited because I, from one side I want to, I can come back to my start, starting point and I can share that with the fellows and, and I can suggest them, look, you know, some exercises and some psychological feeling, how, how maybe to look.

Because the worst thing is arrogance. I always say, you know, you should really study music and anything you can. And as soon as you think, oh, I'm a conductor, no, I, that's not, you know, it takes a while until you can say, well, I'm a conductor. Because it's so much you have to learn.

Jeff Spurgeon: But you have learned it, and you'll find your own way to pass it on, I'm quite sure. And you have lots of people who will be looking forward to those performances. We have lots of people who are looking forward to talking to you. So we're going to say thank you for stopping by our microphones. You have a big line of people behind us who'd like to say hello.

Andris Nelsons: Thank you so much, it's a great, great pleasure.

And if someone, I don't know when this comes out,

Jeff Spurgeon: You're on the air right now. We're on the air. Yeah, so it's on the air really soon.

Andris Nelsons: So tomorrow, if you're, I must say, one of the most exciting, you can't even say exciting, but tomorrow the other concert we play is a concertante of Lady Macbeth, which is, which we played two times in Boston and also recorded. This is a wonderful cast. This is something very special.

John Schaefer: Shostakovich.

Andris Nelsons: Shostakovich tomorrow, so if, if there still are tickets and you still want to, to hear a, thriller.

Jeff Spurgeon: All right.

Andris Nelsons: Musical thriller then you're welcome tomorrow.

Jeff Spurgeon: All right. Thank you. Thank you, Andris Nelsons. You've talked about your performance tonight, a little work on conducting, and you plugged tomorrow's concert.

John Schaefer: Well done.

Jeff Spurgeon: You've done a lot just in the last few minutes.

Andris Nelsons with us from Carnegie Hall Live tonight. We're so grateful to the staff of Carnegie Hall and to Clive Gillinson for our concert performance tonight.

Engineers working on this project this evening include Edward Haber, George Wellington, Bill Siegmund, and Duke Marcos.

The WQXR production team is Eileen Delahunty, Laura Boyman, Aimée Buchanan, Maria Shaughnessy, and Christine Herskovits. Thanks to our colleagues at WCRB in Boston and producer Brian McCreath for the interview we heard earlier with Seong-Jin Cho. I'm John Schaefer.

I'm Jeff Spurgeon. Carnegie Hall Live is a co-production of WQXR and Carnegie Hall in New York.