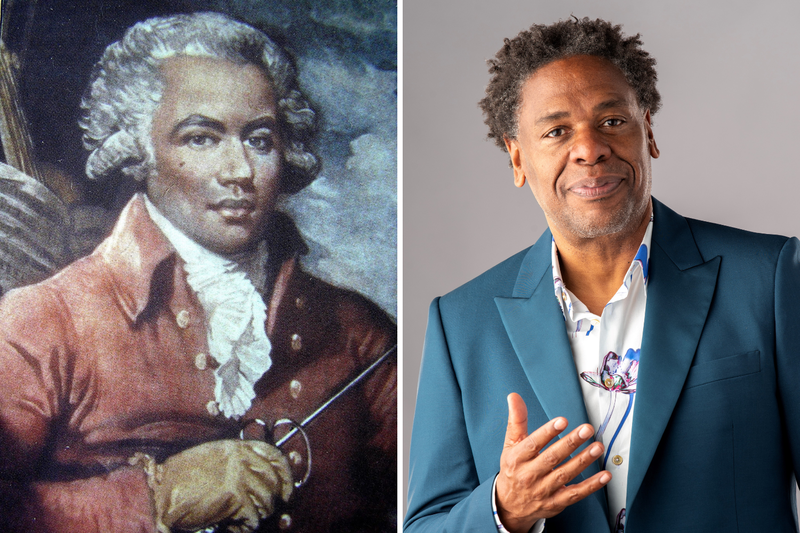

( Photo provided by Terrance McKnight )

Terrance McKnight: I want you to imagine a knight. K N I G H T. Yeah. Knight. Imagine a knight who could swim with one arm, a knight who could split an apple with a bullet from a pistol while the apple was on top of your head. A knight who was a fencing champion at age 16 who went on to lead a regiment during the French Revolution.

This man was born enslaved but went on to fight for the abolishment of slavery. He was a phenomenal violinist, a brilliant composer, and a groundbreaking conductor: Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

He led a life that reads like a screenplay, a real-life superhero, but his true legacy is largely missing from history books. So today we'll learn more about this formidable man with some of his music and some conversation we'll hear from violinist Lady Jess. We'll be communing with the Chevalier's music. We'll hear from Bill Barclay. He's a UK based playwright and musicologist. But first, let's go back. We're going back to one of my favorite places on the globe, the island of Guadalupe, whereas Joseph Bologne was born. I'm Terrance McKnight, and this is Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier of Music and Revolution.

So, a couple of summers ago, I'm at JFK Airport about to take off from my summer getaway. While I'm sitting at the gate, I ran into a young man that I knew from New York's music scene: conductor, Marlon Daniel. As fate would have it, we were both heading to Guadalupe. I was going there for vacation. Marlon was actually going there to start work on a festival that celebrates the life and work of Joseph Bologne.

Oh, it was terribly exciting. It wasn't my first time going to Guadalupe. I had gone there before looking for traces of the Chevalier. It wasn't Marlon's first trip either.

Marlon Daniel: First time in Guadalupe was in 2011 when I was doing an experiment to find out if it was viable to have, uh, a festival about Saint-Georges. Well, in Guadalupe, he is a kind of a national hero. Um, they have streets and schools named after him, and, uh, Guadalupe has never forgotten Saint-Georges, even if the world has, because he's one of their like, uh, Del Grais and a couple of other people who came actually from Guadalupe. Their name in history have been all but forgotten in some cases, but people of Guadalupe never forgot because for music it stands out.

He predates Mozart and he made such an impression on Mozart, Haydn, C. P. E Bach, and if we like, trace it all the way to like the 20th century Prokofiev, classical symphony, and things like that. And so that's how it kind of all started.

Terrance McKnight: So, these days in Guadalupe, is Chevalier respected as, um, is he revered as a musician, uh, for his work around music or more as a revolutionary as a soldier or colonel?

Marlon Daniel: He was realized as both. Um, we have to realize that Saint-Georges was like a Superman of this time. I mean, he inspired like Dumas. I mean, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, Dumas's father was actually in his regiment, the Legion of Saint-Georges, which was a legion, uh, you know, a platoon of, um, Black soldiers. That pretty much, you know, saved France's butt a lot in that time when they were fighting and um, and this like inspired, it's like no doubt in my mind that he inspired D'Artagnan because who, when you think of these things, sometimes real life is actually better than fiction. And he was a real life D'Artagnan.

Terrance McKnight: So, Marlon, let me get your opinion on this. He was a great fencer, a great athlete. Now, do you think he just had a proclivity for those things or did his father give him those lessons to protect himself? I mean, he was, you know, in danger just being a person of color and being somebody who was so, uh, such a socialite. What do, what's your opinion about that?

Marlon Daniel: Well, of course, in France they had the Code Noir which was kind of like our Jim Crow laws. And, um, I, I believe that his father actually loved him. His father didn't have any other sons.

And also, his father was trying to, in one way, protect his legacy, protect their name, you know, getting a, you know, a knighthood. You know, being aristocrats, you know, he was wealthy. Wealthy from the slaves and the slave trade and the sugar cane and things like that. But I think the father wanted to be remembered too.

And the way to remember that is through your offsprings, he got, uh, the young Saint-Georges like lessons at La Boëssière School, which was like a kind of a, a boarding school for the aristocrats. And through that, you know, education, he, you know, the payment of the best education he could find for his son. He excelled in everything.

And I think he also excelled because, you know, you know, he was referred to at La Boëssière as mulatto, you know, and he had to, like, in modern days, you know, you always say that, you know, at least people of color always say you have to really be the best because you know, you're dealing with a world that's not exactly appreciative sometimes of artists and people of color. So, you have to work a little bit harder to stand out and I think that that was pretty probably true even in that day.

Terrance McKnight: So, what else have you found out, you know, through your time in Guadalupe? Any discoveries about his, his personality or his character in that time?

Marlon Daniel: I can't really comment on his personality. I only can like make conjectures from the things that he's done. Obviously, he was somebody with a very high moral standard. Obviously because of, uh, his mixed race or whatever he felt, I'm sure, he felt black. He felt, he felt like, you know what with this whole thing with the Code Noir and Napoleon and slavery and things like that, he felt, I'm sure a part of, or an exponent of that and trying to make things better.

So that says to me that, you know, he was also in some way kind. He, he not only talked the talk, but walked the walk. I mean, you didn't see Mozart or Schubert, or even Beethoven going to war. You know, for their beliefs, he actually believed in those ideals of France, and I think that that put him on a very high moral compass.

Terrance McKnight: Okay, let's hear some of Joseph Bologne's music right now. This is from 1779. This is from his Symphony in G Major played on this recording by Tafelmusik. Jeanne Lamon is conducting.

MUSIC - Bologne: Symphony in G Major

All right, so let's talk about his music. When we think of classicism, we always think of Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn, the three big classicists. Chevalier was born before Beethoven and Mozart. Talk about that. What do you see in this music? What do you, what do you hear? Not necessarily in terms of how it stacks up against theirs, but, but what you as a conductor, as a musician, learn about the period through his music?

Marlon Daniel: Well, first of all, France was the city of light at this time. You have, um, king Louis and, uh, Marie Antoinette sitting on the Crown. They loved music. They loved everything, uh, about the arts. You know, this was the, you know, the age of Enlightenment. Saint-Georges was the, at the apex of this. He was the most celebrated. He was the most known. You know, Mozart came there in 1778. He couldn't even find a job. This is the reality. Now, we look at the Austro-Hungarian. And we see, of course, Haydn and Mozart and then further in Germany, you know, Beethoven. But France doesn't have a place and that's because, you know, the French Revolution where it was kind of like an all or nothing. We're changing. Out with the old in with the new type of mentality. But Saint-Georges influenced them all because this was the dominant music. Because of history in, in the turmoil in France, it's sort of been erased. I mean the Austro-Hungarian Empire controlled classical period: Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn.

But really in reality, they all were trying to get to France because France was the place where it was all happening. And at the apex of that was Saint-Georges. And so, France has a big stake in the classical period in the 18th century music, but they haven't really embraced as much as they have because before there wasn't a lot of music, but now as things are being discovered and they, they're finding out about Saint-Georges it's like, wait a minute. Well, the master of the classical style maybe it was actually France.

MUSIC – Bologne: Ernestine

Terrance McKnight: Music from Chevalier's first opera, Ernestine, that was written in 1777. You heard soprano, Faye Robinson, with the London Symphony Orchestra, Paul Freeman conducting. I'm speaking with Conductor and Chevalier historian Marlon Daniel. There's a story associated with St. Georges in which Marie Antoinette wanted to appoint him head of Paris Opera and the, and the singers kind of balked against that. Didn't want this, uh, Black man to be in charge that way.

Marlon Daniel: He was offered this job, he was up for it, but he also had a sense of duty and a sense of humanism. And he was very close to Maria Antoinette because he was doing a lot of music.

She was into music. This was great. Um, people even say that there was a little bit more going on. We don't know that. That's never been proven. But, you know, when these three ladies, the three divas of the opera, you know, they, it was clearly, they said basically they don't want to work under a black man. And that is a clear act of racism, you know. And you know, for spite, by the way, Louis, actually retracted that whole job.

He's like, you know what, you know I built this hall and all these things, but since you're not going to have Saint-Georges, you know what you, it's not going to go to somebody else. It was like jobs off the table. And he actually saved the face of Marie Antoinette and all the, and also Louie at the time, because you know, he's like, "I politely decline." He was sort of above that.

Terrance McKnight: However, Joseph Haydn, when Haydn brought his music to Paris, to the Chevalier, who had gone to Austria to meet Haydn and talked him into coming to Paris. I find it interesting; you don't hear about any discrimination towards Saint-Georges in the 1770s when he conducted those Paris Symphonies.

Marlon Daniel: Yes. Yeah. The, the, the Paris Symphonies, actually, that was a commission not only with Saint-Georges, like so prolific in his own music, but he was helping out people like Haydn. He commissioned those and performed them for the first time in Paris.

Terrance McKnight: Yeah, man, Haydn was so excited to go to Paris. This was the biggest orchestra to have played his music up until that time. I mean, there were like 40 violins in that orchestra.

Marlon Daniel: Yes. I mean, and I mean, not one symphony, not two, but six symphonies. He was on top of everything. And I think that that's another thing that attracted people like Mozart to come there. They wanted to get on this, this boat, you know, uh, try to, you know, expand. Mozart wrote his Paris Symphony at this time, which was trying to, you know, appeal to the Parisians. And who was, who was the main Parisian you want to appeal to? The one who was getting concerts done and that was Gossec and, uh, subsequently Saint-Georges.

Terrance McKnight: Okay, so you've already talked about Mozart. He was in Paris looking for work. He was about 21 years old. Very difficult trip. You know, his mother died on that trip while in Paris. She was there with him and shortly thereafter, he's in a house. Several people, Chevalier is in the house. Now, Chevalier had some of his performances going on, performances of his music in Paris at the time. He was very busy, and Mozart was trying to find his way.

Mozart had already written his Paris Symphony, uh, that Spring. So, what do you think? What do you think of those conversations? What may have happened in those conversations or the music making? Do you have any idea what was going on in the house where Mozart and Saint-Georges were living together? If they performed together, did they show up on the same bill? Any sense of that? Any comparison between the two at the time?

Marlon Daniel: My thing is that Mozart could not have been a tabula rasa in Paris. He had to hear something. In the concerts that were going on, even with the Haydn symphonies and the things like that, he had to hear something. I mean, his whole style changed after he was influenced by France.

I think that, you know, the, the comparison becomes because of they were born around the same time that, you know, 18th century and, you know, the Mozart noir, the Black Mozart they use tried to use this misnomer, which I think you know, a little bit of systematic racism system here. Because whenever you compare something to something else, usually the latter is inferior.

The misnomer, it's like a backhand, um, compliment. You know, at the time of Mozart and, and Haydn, no one ever called Saint-Georges that. Never. It wasn't something that was matriculated at that time. You know, we just started that now, and I think that, of course, Saint-Georges should be on his own. Of course, Mozart is a supreme genius. I love Mozart. He's one of my favorites. But even today, people like to think that the people just were born with it. They sprang out the womb doing what? Playing piano, playing violin, whatever. But there's a lot to say for what your environment was, who your teachers were and things like that. That all goes into it. What you use and how you use it afterwards is what makes your genius come out. But in this case, you know that catalyst for Mozart at that time was Saint-Georges, so he should be considered an independent composer and not the something of something.

Terrance McKnight: Not the something of something. My big thanks to Conductor and Chevalier expert Marlon Daniel, I'm looking forward to catching up with him sometime in Guadalupe for that festival.

MUSIC

A work by Chevalier, which translates to “The Other Day in the Shade” sung by Patrice Michaels Bedi with Forte Pianist, David Schrader. I'm Terrance McKnight, and this is Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier of Music and Revolution. You know, there was some interest about Bologne's life in Boston a few years ago. Musicologist and playwright Bill Barclay was commissioned by the Boston Symphony to create a production called The Chevalier. Now, this premiered in Tanglewood in 2019, and it imagines the world of Knight Bologne in Paris and his interactions with his music student, Marie Antoinette and his new roommate, a 21-year-old Austrian upstart named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

EXCERPT – The Chevalier

I brought Bill Barclay on the program to talk about his project and his findings on Bologne's life. Now, do you remember the first time you heard Bologne's name? In what context? Where were you? What were you doing? What was going on? Take us back to your introduction to Joseph Bologne.

Bill Barclay: I had a meeting with Margaret Casely-Hayford, who's the chair of the Board of the Globe and Chi-chi Nwanoku, who's a British, Nigerian double bass player in London.

And they came to me with the idea of doing some kind of performance about Joseph Bologne and I said, who is this person? And didn't know and was promptly embarrassed as they told me a brief history of the astonishing biography of this astonishing man. And I remember my jaw sinking more and more towards the floor, astonished at his athleticism, about his musical story, that he was the best fencer in Europe, but also virtuoso violinist, and that he was the general of the first all-black regiment in military history, fighting for the French and the French Revolution, and uh, also fighting of course for the abolishment of slavery.

And that began a two-year odyssey to this moment where I have spent my time trying to figure out, why I didn't know about this guy as a music historian, as a musicologist, and how we could collaborate on creating the right vehicle for the world to understand who this person was and why we didn't learn about him before. And since then, it's just been, uh, it's been a rollercoaster learning all of the dimensions, all the places that this man's life has touched and understanding, trying to reckon with why I didn't know.

Terrance McKnight: So now let's go back and tell us about your play the Chevalier. Set it up for us. Give us a synopsis of where you go in this.

Bill Barclay: So, in 1778, uh, Saint-Georges is about 32 years old, and Mozart has just arrived in Paris. His mother has just died. He has no job. He's sick with the flu, and he literally gets dumped into the Chevalier's house.

We don't know why Baron Graham brought Mozart into Saint-Georges's life. We don't know why he thought that Saint-Georges would be the person who could nurse Mozart back to health, but for six months, Mozart and Saint-Georges are roommates in Paris. What they might have given each other, the conversations they might have just opens the playwright's mind, as you might imagine. Now at the same time, Saint-Georges is the private music teacher to Marie Antoinette and she's valuing him, and she wants him. Marie Antoinette is, uh, was actually very, very good sight reader. Great harpsichordist, of course, brilliant harpist, loved to sing, loved to make chamber music, and they forge a bond.

Now, Marie Antoinette and Mozart are peers. They're about 10 years younger than Saint-Georges, and so we have immediately this very interesting triangle where all three of these people are immigrants. Mozart and Marie Antoinette are immigrants from Austria. Saint-Georges is an immigrant from Guadalupe. And you have three immigrants who are trying to claw out respect among the French during a time of severe racial unrest.

There's a registry of black people that's going on at that point. Uh, Ponce de la Grave is registering the addresses of black people, is threatening to expunge them and make it illegal for them to ever come back to Paris once they leave France. Marie Antoinette is being assailed for her Germanic background as well, all the cartoons about her being Austrian.

So, my story begins with three people who are trying to find respect in Paris and Mozart and Saint-Georges form a bond in the first half of the play. Saint-Georges meets de Laclos, who at that point is trying to conscript Saint-Georges to join the early resistance and to fight ultimately in the French Revolution.

And at the end of the first half, Saint-Georges has to decide whether he's going to be loyal to the Crown as knight of the king and a friend, an ally of Marie Antoinette, or whether he's going to actually throw his hat among the resistance and fight to topple the monarchy, to assert a constitution and to help France move forward in the New Republic. He has that big decision to make at the end of the first half.

EXCERPT - The Chevalier

Terrance McKnight: So, there's a story of John Adams being in in France. He had come to talk about a treaty in the 1770s, and apparently, he saw Chevalier perform and he wrote in his diaries, oh, this is the most accomplished man in Europe in fencing and riding and climbing and jumping and playing piano and violin. Can you set that up for us?

Bill Barclay: So, John Adams comes to Paris in many ways to continue the diplomatic relationship with the French revolutionaries, Lafayette, many of them who had given money and soldiers to the American revolutionaries and helped them win their Revolutionary War, but doesn't stay very long in chiefly, is coming to bring Franklin back home.

And meets with Marie Antoinette and happens to see Saint-Georges and is completely overwhelmed with his polymath abilities. And so, in my play, Saint-Georges comes in to see Marie Antoinette in one of his music lessons and there's John Adams. And John Adams just has a complete fanboy moment all over Saint-Georges and makes him uncomfortable and Saint-Georges decides to use the opportunity to say, and what are you doing about equality in the United States?

And John Adams says, compromise is a very difficult process. And Saint-Georges says, yeah, three fifths of a person does sound rather difficult and painful, doesn't it? And so, they have a meeting of the minds. Saint-Georges is intent upon abolishing slavery, and everybody knows Americans pass the buck on the abolishment of slavery. And everybody knows that the French Revolution can't make the same mistake and they do. So, I use this moment- John Adams saying he's the most accomplished man in Europe at all of these things-I use it as an invitation for a conversation to show the audience a conversation between these two men about their priorities.

Terrance McKnight: So, by this time, Chevalier was well known. Um, talk about how he got to be so well known. Was it as an athlete? Was it as a swordsman? Was it as a musician? When did he gain such notoriety and how?

Bill Barclay: So, he's 16 years old, so this is 1761. He is the fencing protege of La Boëssière, who's one of the great fencing masters in Paris. The Seven Years’ War has just ended. This is the war that France lost, Canada and India, and several other major assets in Africa, and the French were very bruised. And there was a contingent of nationalists in France, you could call them nationalists, who were blaming the French losses on a lack of Frenchness.

So, there was a moment of racial unrest and tension, uh, in Paris that was being left unchecked by the crown. And outside of that, uh, sort of broiling temperature, Alexandre Picard, who was a racist bigot, he was another fencing master in Paris who made, uh, uh, public fun and mockery of quote unquote, Boëssière’s Mulatto, and Boëssière taking umbridge obviously encouraged Joseph, knew how good Joseph was a fencer, encouraged Bologne to challenge the fencing master Picard to a duel. So, he does. And Bologne makes quick work of him. 16-year-old, um, mixed race guy no one knows about. Can you just imagine how beautiful and incredible this duel must have been?

And from that moment on, the king is so delighted that he just makes him a knight of the private guard. He makes him a Chevalier de Saint-Georges and suddenly the the Bologne's fame skyrockets and he becomes the fencer to beat in all of Europe for the next 30 years. It was six years later that he makes his debut as the fastest violin virtuoso in Paris. And you can just imagine how his fame increases from that point.

Terrance McKnight: So, you know, why has he been buried in music history for so long, even to people who study music in school? Why, why has this figure been buried?

Bill Barclay: I think there are a few reasons. It is tempting to ascribe the fact that we don't know him entirely because he's black. And I think of course that is a huge reason. Uh, there's definitely a centering of white experience in history, retellings of all kinds and music history is no exception to that. But as I started to study French Revolutionary History as it related to music, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars really curtailed all of the great developments in French music and a lot of French arts that were happening in the 18th century.

The French Revolution really just completely tore up the topsoil of the talent that was happening during that time and, uh, and destroyed the pipeline of young talent and made it hard for people to get performances at any skill level for 40 or 50 years. Much of Saint-Georges's music that has apparently been written isn't streamable isn't purchasable. It's very hard to come by audio recordings of even music that has made it to us. He's got, uh, string quartets that haven't been recorded. There are a couple operas that are entirely gone because of course, the French Revolution burned just plain and simple, burned a lot of the buildings and so many records were lost.

But he himself stopped composing instrumental music partway through his life in order to take up the cause of the abolishment of slavery in order to create this regiment, um, of free black men to fight against Austria and defend France in the revolution. And so, his life was cut short artistically through his other passions.

So, it's a, it's a race issue. It's also a historical issue. It's a war issue. There's a lot of what France gave music in that period that is lost, and along with that loss is Saint-George's place in our history. But there's one other thing I'd love to mention, which is his musical legacy as it relates to what he gave Mozart. In his string quartet writing, he moves the melody around the parts quite a lot, flattening the hierarchy of the first violin as the leader. He also really creates the Symphony Concertante style of having two or more soloists soloing at the same time like a good duel. And Mozart's Symphony Concertante in E Flat takes quotations from Saint-Georges's Symphony Concertante. In his violin keyboard, sonatas, he gives the melody all the time to the keyboardist. It's as if he doesn't want to have a leader. It is as if he is practicing egality. In his music, coding democracy.

In his writing, we have this desire to watch equally matched soloists sharing the limelight, and it's my opinion, and this is what I explore in my play, it's something I believe he gave to Mozart. That we don't always want to see one genius being the beacon and having everyone else follow them. Why don't we flatten the hierarchy of the music and see the genius spread around? See a good duel happen, see a conversation among equals happen. So, I think he is coding equality in his music, in his compositions, which I believe is his activism before France erupts in Revolution.

EXCERPT - The Chevalier

So, the French revolution means the execution of Chevalier's student and friend Marie Antoinette. Chevalier because he's a knight and seen as part of that nobility. He was imprisoned.

Bill Barclay: He suffers in prison for 18 months. During that time, Paris abolishes slavery in part because of the uprisings of the African slaves that were brought to Martinique and modern-day Haiti.

Those uprisings that burned the sugar crop fields. And made it impossible for the French revolutionaries to make money off the islands. They decide then to abolish slavery in France and the colonies. It's, it's always about following the money, you see. Saint-Georges knows this, Alexandre Dumont knows this, and he retires to a smaller community and plays his violin.

He has the best ending of any of them: Marie Antoinette, Mozart, de Laclos, Napoleon. The Chevalier wins in the end.

Terrance McKnight: That was Bill Barclay. He's a musicologist, a playwright, and currently the artistic director of Concert Theater Works. You also heard excerpts from his play, The Chevalier with Chukwudi Iwuji as the Chevalier, David Joseph as Mozart, and Bill himself as Choderlos de Laclos. Let's hear more from Bologne. This is his Concertante, the London Symphony Orchestra with violinist Jaime Laredo Miriam Fried, also playing violin conducted by Paul Freeman.

MUSIC - Bologne: Concertante

Joseph Bologne's Concertante. So, what's it like to play Mozart's music alongside Chevalier? So, for that conversation, let's talk to this musician. She's a violinist. She plays Mozart and Chevalier. This is Lady Jess.

Lady Jess: I started playing violin when I was eight years old.

Terrance McKnight: How soon after that do you think it was before you heard the name Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart?

Lady Jess: Oh, it was in the first year of studying violin. Definitely within the first few months.

Terrance McKnight: Mozart is one of those early composers you get to as a violinist time.

Lady Jess: Yes. I was a Suzuki student, so I used a specific pedagogy, but Mozart was included in that repertoire from the very beginning. So, I learned about Mozart. Mozart was one of the first composers that I ever learned about.

Terrance McKnight: The name Joseph Bologne the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Do you remember when you first heard that name?

Lady Jess: Um, yes. The first time I heard the Chevalier de Saint-Georges was in 2013. I was hired to play for a music festival that had been structured around the works of the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. So, it was for a gig. It was a gig that I care very much about, but I learned about him so as to be prepared to show up and participate in the music festival.

Terrance McKnight: Yeah. Now, I don't mean to delve into your personal life story so much, but I just want to draw this parallel because like Chevalier, you are the product of an interracial relationship.

Lady Jess: Yes. My mother is white, and my father is black.

Terrance McKnight: I'm wondering, Jessica, how meaningful would it have been for you as a young person? Maybe not eight years old, but as a 13-year-old or as a 18 year old being introduced to the works of Chevalier, someone who shared life experiences with you as an interracial person? What do you think? What do you think about that? Am I just making something up?

Lady Jess: No. I began playing the violin because of representation. I saw a little black kid playing on Mr. Roger's Neighborhood, so seeing that is the thing that started me in the first. If I had known, especially since as a kid, I really didn't like practicing. I had to be pushed to practice all the time. And so, if I had known that, there was the kind of music that sounded like everything else in my Suzuki book, but that was written by someone that looked like me, no less shared life experiences with me, I think there would've been an emotional connection to the music that would've translated in my child mind as I just want to play it more.

Terrance McKnight: I've seen you play music by Chevalier de Saint-Georges, and as I think back on that evening, it seemed to me that you approached his music with a, a certain type of pride and ownership and understanding and, uh, responsibility. I remember seeing you there with that orchestra. Can you talk about your experience in playing someone like Chevalier versus playing Mozart? I know you played both, but talk about ownership of the music and, and the type of, I don't know, just the personal experience for you, uh, dealing with those two composers.

Lady Jess: I know that when I studied Mozart, I felt, I always felt like I never had a chance to really learn to love the music, because as a violinist and any, actually any string player will tell you composers like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven these are composers who your educators, and empress on you as being arbiters of all of this, and you must learn it and you must learn them in this particular way. And so, I would find melodies written within Mozart's music, you know, The Turkish melodies, for instance, in the third movement of the fifth violin concerto.

Those things would speak to me, and I would love them just on an artistic level, and then I would take them to my lesson and all the life would be sucked out of them because who cares about that if you can't get the technique first, and then the technique becomes the standard as opposed to the music being the standard.

The technique is the standard. I found that in college, the only way to pass any sort of practice audition, whether it be in an orchestral excerpt class or in a private lesson, would be to simply mimic the recordings. And so, I learned whatever technique I learned to mimic what I thought a particular panel would want to hear.

And so, in that way, the artistry, the music, the creativity, it all takes like a backseat at the back of like a tour bus at the back of a Mac truck is so far back, you know? So, I used that same energy to prepare technically for the Chevalier de Saint-Georges Concerto in G when I applied the same technique that I used to prepare the Mozart concerti to the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, it still wasn't enough to get the concerto to performance level. It is such a difficult catalog of, of music and it's such a difficult concerto, and there are things the Chevalier wrote into the concerto that mirror difficulties he had in his life. So, for me, at that age, I was like, not only do I want to play this perfectly, I want to play this perfectly so that there can be no question of the validity of the works, of the Chevalier being part of the standard canon, being part of standard audition repertoire of which it is not. Um, periodically there's an arts organization that's devoted to Black and Latinx classical musicians, and they have an annual competition and they will periodically program, um, music by Saint-Georges in the preliminary rounds. And so, you can say the music is there, but if it's not in the final round, which is broadcast to an international audience, it is A never getting exposure, and B, in the minds of the students who are competing, never placed at the same level of importance as like the Mozart five violin concerto.

Terrance McKnight: Yeah. So, let's say there's an audition for an orchestra coming up. Would you rather see personally for yourself, would you be attracted to the orchestra who's asking for a Beethoven, a Tchaikovsky, or a Mozart concerto or the orchestra that's asking for the Chevalier concerto.

Lady Jess: I'm not even going to consider auditioning for the orchestra that is asking for the Mozart concerto. I'm not. I'm moving on because if I don't see works by people that share my cultural and racial experience represented in the standard canon, then I don't feel welcome. And so why then would I invest my time in that model? Whereas if you're putting music by the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, it demonstrates that your ensemble has a vested interest in, uh, cultural equity. And so, I'm, I'm heading in that direction.

Terrance McKnight: You said something earlier about Chevalier. You could hear, I mean, in his music, you can see like his life. You can see the, the tension. You can perhaps hear the pain, the struggles that he went, uh, that he went through. How do you, how do you write that musically? Uh, Lady Jess, what are you, what are you hearing in that? What are you seeing in the writing that suggests the struggles he went through.

Lady Jess: I also wrote my own program notes for that performance. So, I ended up studying a lot about his life and subsequently crushing on a historical figure because he was so multifaceted. There are legends that say he used to swim the Seine on with one arm every morning.

Um, he was a champion sword fighter. He also was influenced by François Torres. And influences of Torres' bow technique are written throughout the concerti. They're some of the hardest things about his concerti. And when I play the piece, because at the time that I was preparing the piece, I was also teaching full-time, and I would play little excerpts for my students because they made me the most nervous.

So, I'd get my performance practice in with them just randomly and, and quiz them on, you know, whatever I was writing on at the moment. And a lot of them would say, it sounds like he's fighting. It sounds like swords. It sounds because the bow would be moving so fast. I would ask them to watch my bow arm and tell me what you see.

And they say, it just looks like, it looks like swords, it looks like wings, it looks like, you know. And so, you can not only here the fighting, the sword fighting and the back and forth, and you can see it in the performance. You can see it in the bow arm. So that's written in the music. I personally saw a lot of contrast in the way the outer movements have more of a very traditional classical sound, and the inner movement is a largo, and so in structure it's traditional, and it's true to form. But the second movement has more of a minor sound, and he implements this technique where in the orchestra is doing this very low ostinato and the violin is floating above. And few classical composers were even writing in that range for the violin. It's very unheard of for that period to be asked to play lyrical slow melodies. So, in the stratosphere almost.

He would write in things like slow broken tenths, slow broken octaves. It's so hard to play that in tune. And so, I found that the second movements were more operatic, and that was unusual. And I think what I pulled from that was this paradox of birth. His mother was from Guadalupe, you know, his father was free and an aristocrat, and there's constant, "where do I fit?" So that paradox of being someone of an unattainable class because of birth, and then being thrust into that world through birth, being talented enough to be fluent and social enough to be moving around in that world, but never actually will be able to make it to that same class or status that even someone like Mozart had.

You can hear all of that in one concerto by the Chevalier, in addition to the paradox of just living as a Black man at court in Paris.

Terrance McKnight: Yeah. My God. I mean this, here's a man who by law couldn't even get married, you know? I wonder what it means for your students, Jess, when you teach when you work with young people and you present the Chevalier and you tell a story to these little brown or white kids, doesn't matter.

Um, I wonder what the breakthrough is for them. You talked about what the breakthrough could have been for you as a young person. I wonder, do you see these stories or this story inspiring, you know, young people differently, you know, and all of a sudden, they see someone who might look like their uncle or someone who might look like dad, um, who's a hero from, from the past in classical music?

Lady Jess: I definitely think so. I know that for so many Black Americans, part of the American experience is trying to figure out our culture beyond a certain point, trying to understand our ancestry because it was lost. I know that when I show videos of music by composers like the Chevalier to these kids if they share complexion, it gives them a sense of ownership. So, for me, at the time, what was really interesting is that I did have students of color in Harlem and I, but I was also teaching, um, a class of students in Chinatown. And they were all, they were all Chinese saved for two, um, who one, one student was Dominican and the other was white.

These kids were, um, living in Chinatown. Their parents were immigrants and they lived in very close-knit families. They were very proud of their culture, very culturally aware. Um, and their instinctual reaction to this music is no different than their reaction to the music of any other composer. What it came down to was how it was presented.

My students learned music faster when they were excited by what they were hearing or when they were curious. If they had never heard it before, they were doubly curious If they saw me playing it, they were completely in.

Terrance McKnight: Lady Jess is a violinist and co-artistic director of the Urban Playground Chamber Orchestra. You can find out about all these guests and the music you heard tonight if you had to wqxr.org. Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier of Music and Revolution was produced by Rosa Golan, James Bennett, Eileen Delahunty, and myself. This is a production of WQXR in New York.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.