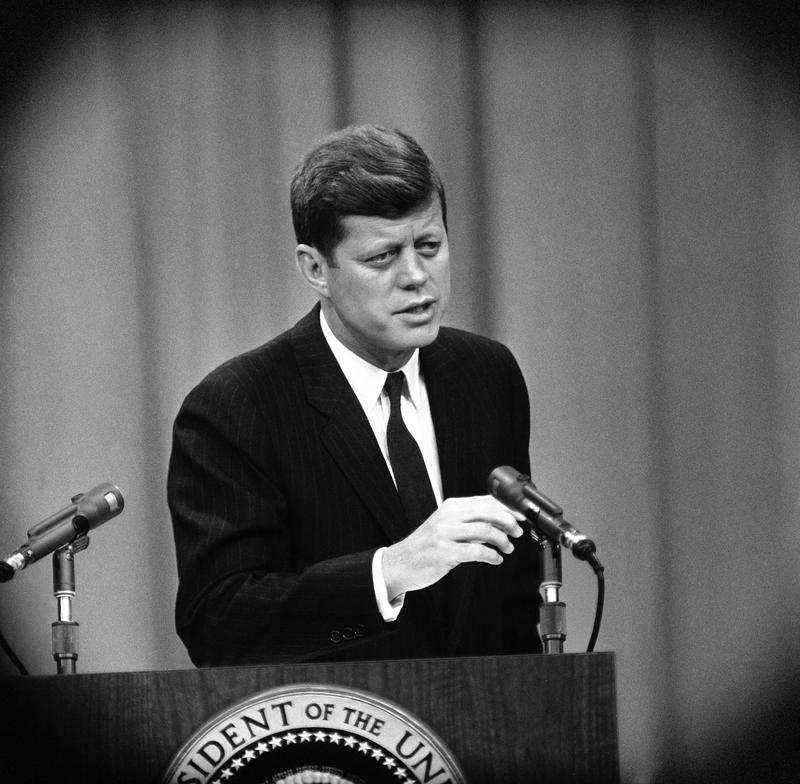

( AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Remote learning 10:00 AM to noon. History classes in session with none other than the acclaimed historian and journalist Jon Meacham, formerly editor in chief of Newsweek, seen frequently on MSNBC during the Trump years, as many of you know and through today, and now the host of a five-episode podcast series, called Fate of Fact. The final episode just came out this morning.

Jon describes the series as being about the origins of the strong grip, misinformation and disinformation have on our politics, with an emphasis on why the right has chosen to break with a governing consensus that however imperfect was once embodied by what he calls the figurative conversation between Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan. In fact, before we even start talking to Jon Meacham, here are two clips from the first episode of Fate of Fact. This is President John F. Kennedy, from when he was in office, early 1960s, governing on optimism and what is in our control.

John F. Kennedy: Our problems are man-made. Therefore, they can be solved by man, and man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man's reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable and we believe they can do it again.

Brian Lehrer: Kennedy invoking reason and spirit, and of course, he was assassinated in 1963, after which his Vice President Lyndon Johnson won election in a landslide in 1964, and proposed an array of social programs aimed at reducing poverty that he named the Great Society. Here's LBJ.

Lyndon B. Johnson: You have the chance never before afforded to any people in any age. You can help build a society, where the demands of morality and the needs of the Spirit can be realized in the life of the nation.

Brian Lehrer: With that, we welcome Jon Meacham, host of the five-part podcast series called Fate of Fact. Jon, is always great when you're on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Jon Meacham: Thanks so much. I hope the pledge drive is going well.

Brian Lehrer: Thanks a lot. Want to put those JFK and LBJ clips in context and tell us why you included them?

Jon Meacham: Sure. There's always a danger in arguing that there was a golden age. There was never a once upon a time in American history, there will never be a happily ever after completely, but there was this moment, at the end, in the wake of World War II, where Kennedy and Johnson and yes, Ronald Reagan, believed that there was this consensus in the country that the country that had won the Second World War that was at least on the Kennedy Johnson side that was attempting to expand the definition and application of human liberty. That there was this idea that we could in fact, in the phrase of Theodore Parker, we could bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice.

That may sound homiletic, but as you just played, it actually was a deeply held view.

When Ronald Reagan in 1964, gave his great speech for Barry Goldwater that really launched Reagan's political career. It is an impenetrable speech in some parts because he's so devoted to statistics, to facts. He wanted to deal with those facts in a very different way than President Kennedy or President Johnson, obviously, but they were living in the same universe. It didn't occur to Ronald Reagan, for Barry Goldwater to claim that the 1964 election was stolen.

There was a sense that the constitution for all its imperfections, provided the rules of the road, pick your metaphor, the buoys of our lives, the guardrails, whatever it is, and the politics was a mediation of differences, not an apocalyptic struggle.

Brian Lehrer: What does the title of the series mean, Fate of Fact?

Jon Meacham: Fact was a relevant and controlling force for American politics with some exceptions, until really the last five or six years. My argument is that Donald Trump was the match that hit a garage floor that had a lot of gasoline spilled on it. There's always a paranoid style. There's always a French, there's always an extreme in American life. The John Birch Society, that was the QAnon of the Cold War.

There's always some extreme that in Richard Hofstadter's phrase is "Paranoid, believes the country is in the hands of unseen forces that are penalizing and trying to dominate others". What is so striking today, and I would not have argued this five years ago. I don't always practice what I preach, but in this case, it's always better to hear a sermon from a sinner than a saint, isn't it? Which is good, given the relative proportion of those--

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] In the world.

Jon Meacham: Exactly. I thought Trump was in 2015, 2016, even into 2017, 2018. I argued, quite vociferously, that this was a difference of degree not of kind. That Trump represented a right-wing, nativist, extremist, racist, nationalistic, populism that was deeply rooted in American history. I still believe that. What is different and what the evidence of the last five years has shown me, particularly after January 6, is that the Republican Party, not just the right-wing, not just the extremes, but a major political party, the party of Eisenhower, and Nixon, and Reagan, and Ford and the Bushes, and I suspect a lot of your listeners think that all those people were terrible, but in a comparative sense, they were not. They believed in the mediation of differences.

What has changed is that 60% of one of the two major governing parties in the United States believes a lie, a self-evident lie. Not even a very close call of a lie, which is the stolen election. That's just the death of fact, right? That's it.

The Fate of Fact, so what was it? What led not there to be an extreme at work in American politics. There's always an extreme at work in American politics. What made the center part of that party lose its mind? As I was thinking about it, and this podcast, and what we're talking about is simply my opinion, so take it or leave it. Is that there has been a building frustration among conservatives, among those who believe that the marketplace except when it helps them should take primacy over the state. Those who held basic Republican views. They have been frustrated, and it's been a multi-generational story.

Eisenhower appoints Earl Warren. Warren gives the country blessedly and wonderfully, the brown decision and the enforcement decision and the Miranda decision, the 1962 School prayer decision that took sectarian prayer out of the public schools. Nixon comes in, he runs hard to the right, and what does he do? He falls under the spell for a while of your former senator, Daniel Patrick Moynihan. He creates the EPA, he thinks about a family guaranteed income. He goes to China. Ford governance very much in that consensus.

Reagan, who seems to be the great conservative answer to Detente, and Nixon and Ford. In fact, in 1976 and in 1980, is very explicitly the conservative candidate in a party that was pretty moderate. Reagan challenging Gerald Ford in 1976, and Reagan and George H.W. Bush running against each other in the primaries in 1980, shows that there were viable factions within the Republican Party. That is no more. What Reagan did, of course, when he became president is yes, he dramatically cut taxes in 1981, but then he raised them about five times. I used George Bush's biographer, and he on more than one occasion--

Brian Lehrer: The first George Bush.

Jon Meacham: Yes, George Herbert Walker Bush. George Herbert Walker Bush raises taxes once and gets N. Gingrich and all take over. Reagan raised them five or six times and Bush used to say. I don't know how he got away with it.

Brian Lehrer: One of your episodes is about the rise of the religious right, and how that movement has created to contributing what you call a false choice between faith and fact. What's the false choice and how does the religious right contribute to the rise of that part of trumpism that you're emphasizing here, willing to throw facts out the window?

Jon Meacham: It's self certitude. My strong belief and I am a Christian, not a very good one, is that the central message and what should be the prevailing ethos of the faith and to which I was born in which I had here should be the Sermon on the Mount. It should be the gospel message of love your neighbor as yourself. A radical and revolutionary commandment that is far more relevant in its breaching than in our adherence to it.

The false choice, I believe, is that the religious right has decided that they are under siege. The culture is arrayed against them, and that they have the answer, not an answer. Everybody likes to think they have an answer, but that they have the answer, and their answer leads to theocracy. It's very un-American. America's first liberty, as it's been called, is religious liberty, not just in terms of secular political thinking, but because if you're a religious person, you want religious liberty, because you're not always going to be totally in control, you want your liberty.

James Madison brilliantly as a very young man in Williamsburg Virginia, the Virginia constitution which preceded the declaration, the Virginia Declaration of Rights which preceded the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the proposal that talked about religious tolerance, and Madison changed the word to Liberty, because tolerance presupposes that there is some force that is allowing you to do what you want to do. If you shift it to Liberty, then it's innate.

The problem with the religious and the white Christian nationalism, which is a besetting problem, as is race obviously, which we haven't mentioned, but clearly that is a run straight through all of this, is that instead of following the gospel, which if you're a Christian is a fact. There is a fact that in the drama of your religious views, in defeat, there is victory, in the face of cruelty, you answer it with kindness, in the face of greed, you answer with generosity. That is the gospel.

It's rooted in Leviticus with the love your neighbor as yourself. It is fundamental, and yet, the political manifestation by and large of conservative Christianity today is not about reaching out, it's about throwing a fist, it's not about building a bridge, it's about putting up a wall.

Brian Lehrer: We have two minutes left in the segment, and your final episode, which came out today, is called To Bend The Arc, which is a reference to the Martin Luther King quote, that the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice, but you acknowledge one of the realities in our politics today is that people in both parties don't feel like that's always true. They feel like progress is not inevitable. They challenge politics based on hope that you started with an episode one with those JFK and LBJ clips.

I think it's when there's no hope that people fall into nihilism in politics, and then it's just about destruction of things that they think aren't serving them without necessarily a plan to make things better. Through the lens of all of this history that you report in this series in our last minute, can you see the path for the next round of hope?

Jon Meacham: I can because we've been here before. 150 years ago in my native region in the American South, 11 states of the Union chose to fight and die for human captivity, that was also based on a lie. The lie of racial superiority and a perversion of theology into a pro slavery exclusionary force. That required a civil war and a century of reconstruction, but we live because of the Constitution, and this is why protecting the rules of the road are so important.

I understand the Constitution is imperfect, I understand the structural points. When William Lloyd Garrison burn the Constitution in the 1850s Frederick Douglass said, no, that, in fact, as he put it, "There's no soil more conducive to the growth of reform than American soil." I believe that the source of hope has to be that if enough of us agree with the basic point of what I'm saying, then we need to go into the public arena as you do, and argue it.

You're never going to get 80%, you're never gonna get 100% but let's say instead of getting 51%, let's say we get back to 55%, 56% of the country believing that in fact, all men are created equal and our sacred obligation, our most important obligation is to reach out and not throw a fist and if so, that will be progress.

Brian Lehrer: Historian Jon Meacham, his new podcast series five-part series with the final episode just having dropped this morning is called Fate of Fact, wherever you get your podcasts. Jon, we always learn when you're on the show. Thank you so much.

Jon Meacham: My pleasure. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC, more to come.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.